Warm Memories of Herb Parsons

the "Showman Shooter"

(Click any photo for a full screen image.)

- Herb Parsons, by his son, Dr. Lynn Parsons

- Dedication of Herb Parsons Lake, by Hon. David D. Givens

- Thoughts About Your Dad, by Jack Evans

- Tribute to Herb Parsons given at the International Rice Festival, by James W. Barnett

- West Tennessee Sportsmen's Association

- Herb Parsons Radio Interview

- The Herb Parsons Trophy

- Ad Toepperwein Articles

- Showman Shooter by Lucian Cary, TRUE Magazine, July 1954

- The Old Home by Dr. Wayne Capooth, THE DOUBLE GUN JOURNAL, Summer 2006

- Meet Herb & Lynn Parsons, by Connie Mako Miller, Shotgun Sports Magazine, February 2007

- Showman Shooter: The Legendary Herb Parsons, by Scott T. Weber, American Rifleman Magazine,

June 2009 - SHOWMAN SHOOTER BALLAD written and performed in 2009 by Jeremy M. Parsons, the grandson of Herbert Parsons

- Why We Miss by James Card, Ducks Unlimited Magazine, April, 2010

- John Merrill Olin

- King Buck

- The Glory That Was, by Dr. Wayne Capooth

Note: Articles #11 and 12 are in Adobe PDF format.

If you need the free viewer, click here

HERB PARSONS

by Dr. Lynn Parsons, August 15, 1995

After my father's death, a state lake and park near our home in West Tennessee were named for him and dedicated to his memory in 1964. At that time, four friends whose names I believe you will recognize paid tributes, portions of which I wish to share with you.

Gene Keatley owned a sporting goods company in Beckley, W. Va., and often squadded with my father at the Grand American. He wrote, "Yes, I am glad I knew Herb Parsons. I knew Herb as a man, as the world's greatest exhibition shooter, as an expert trapshooter, but most of all I knew him as a friend, and I treasured his friendship. Herb Parsons was clean and decent in his thoughts, words, and deeds.

When Herb gave his exhibitions at the Grand American trapshoot in Vandalia, Ohio, each year, he created more interest than any other event or any type of shooting. I looked forward to it each year, and each time I saw him it was just as wonderful and just as impossible as the first time I saw him. The name of Herb Parsons will never be forgotten, and the miraculous shooting he did will be remembered and talked about so long as sportsminded people get together.

When Herb gave his exhibitions at the Grand American trapshoot in Vandalia, Ohio, each year, he created more interest than any other event or any type of shooting. I looked forward to it each year, and each time I saw him it was just as wonderful and just as impossible as the first time I saw him. The name of Herb Parsons will never be forgotten, and the miraculous shooting he did will be remembered and talked about so long as sportsminded people get together.

"One of Herb's happiest times was when he had large groups of young boys and girls lying on the ground around the shooting circle so he could see them and talk directly to them. He always told them how important it was to get a good education and to be an expert in whatever they did. He told them to try hard to get to the top of the class, to be a good citizen and a leader in their school, work, or play.

"Herb Parsons will never die in my memory. He left something of value to me, and I am sure the world is a better place for his having been here."

Jimmy Robinson, who needs no introduction, wrote, "I knew Herb, not only as a shooter but as a dear friend, since the time he first shot clay targets. We all know he was the greatest shot of all times, and he was a member of my AllAmerican skeet and trapshooting teams a number of times. I was a judge at Stuttgart, Ark., when he won the world duckcalling championship, and I think this gave him his greatest thrill because he loved to hunt ducks. Herb was a delightful companion and a great teacher for our youth. We all miss him very much."

My father worked for Winchester for 30 years. John M. Olin, chairman of the board of Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation, wrote, "As you well know, Herb was a very close friend of mine. We had many, many happy days and experiences together. I found him to be a true sportsman in every sense of the word. He served our corporation in a very worthy manner, especially his appeal to the coming generation. He was a wonderful marksman with both rifle and shotgun, and I doubt there will ever be a shooter who can even approach his ability and his charm."

My father worked for Winchester for 30 years. John M. Olin, chairman of the board of Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation, wrote, "As you well know, Herb was a very close friend of mine. We had many, many happy days and experiences together. I found him to be a true sportsman in every sense of the word. He served our corporation in a very worthy manner, especially his appeal to the coming generation. He was a wonderful marksman with both rifle and shotgun, and I doubt there will ever be a shooter who can even approach his ability and his charm."

Nash Buckingham: "I knew Herb when, as a youngster, he was ambitious to tackle a dream that became glorious reality. From boyhood he worked to perfect himself as the greatest exhibition gunner the world has ever known. And having myself watched the world's best Carver, Buffalo Bill Cody, Annie Oakley, the Toepperweins, and vaudeville stars, I know whereof I speak. Herb Parsons was a perfectionist summa cum laude. In his more than 30 years of ceaseless international travel for the Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation, Winchester Western Division, Herb Parsons fired millions upon millions of shots 'heard round the world,' earning global plaudits for his magnificent skills, showmanship, and outdoor educational benefits to youth, national gunning morale, and sportsmanship.

Nash Buckingham: "I knew Herb when, as a youngster, he was ambitious to tackle a dream that became glorious reality. From boyhood he worked to perfect himself as the greatest exhibition gunner the world has ever known. And having myself watched the world's best Carver, Buffalo Bill Cody, Annie Oakley, the Toepperweins, and vaudeville stars, I know whereof I speak. Herb Parsons was a perfectionist summa cum laude. In his more than 30 years of ceaseless international travel for the Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation, Winchester Western Division, Herb Parsons fired millions upon millions of shots 'heard round the world,' earning global plaudits for his magnificent skills, showmanship, and outdoor educational benefits to youth, national gunning morale, and sportsmanship.

From motion picture screens and lecture platforms, nations listened and applauded Herb Parsons. He neither needed nor employed professional writers for the quipped wisdom and humorous facets of his exhilarating exhibitions. Hidden from motion picture cameras, it was really the unerring rifle of Herb Parsons that made or unmade scores of heroes and villains of film history.

"Words of an old tribute reach me through the mists of time. 'To every man is granted opportunity for some definite expression in life of some particular virtue. To a few men comes opportunity to express all the virtues. He who has given more of good than of evil to the life he has lived, and carried out of life more love than hatred has, we can truly say, rounded out his career. But when there falls by the wayside one who has never received the hatred of his fellowmen, one who has held for always the love, the admiration, and the respect of his intimates, there is indeed a vacancy mantling his comrades in a pall of sorrow.' When Herb Parsons died, he carried to his grave the heart of every man, woman, and child who knew him well."

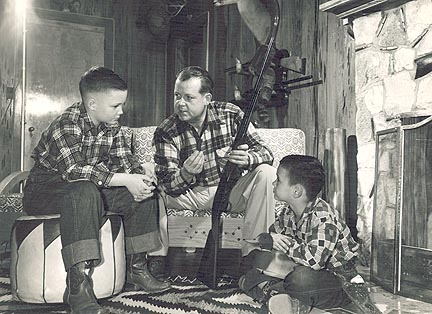

Throughout my father's life, love of hunting and shooting, after love of his family, was the essence of it all. He somehow got me to squeeze the trigger on a .22 rifle so he could say his son fired his first shot at age one. Our bottle weaning was accomplished by his telling my brother Jerry and me anyone still taking a bottle was too much a baby to shoot. We must have wanted to shoot. It worked!

Throughout my father's life, love of hunting and shooting, after love of his family, was the essence of it all. He somehow got me to squeeze the trigger on a .22 rifle so he could say his son fired his first shot at age one. Our bottle weaning was accomplished by his telling my brother Jerry and me anyone still taking a bottle was too much a baby to shoot. We must have wanted to shoot. It worked!

My father's vacation time always somehow fell during the hunting seasons, especially quail in Tennessee and duck in Arkansas. A vacation for him was time spent in the field hunting with his sons or friends. At the end, before his operation for hiatal hernia, his physical stamina was diminished. The last words he ever spoke to us in his hospital bed just hours before his death were, "I've had this operation so I can be well and we can hunt together again."

Most certainly my father still lives in the hearts of the many who knew and loved him. Induction into the Trapshooting Hall of Fame is one of the greatest lasting tributes which has ever been paid to his memory. My entire family and I appreciate it.

Address of Hon. David D. Givens, Tennessee State Representative, at the dedication of the Herb Parsons Lake, July 26, 1964, Fayette County, Tennessee

======================================

This afternoon we gather here under these majestic trees in the sight of this beautiful lake to honor the memory of Herbert Parsons, the greatest exhibition shooter the world has ever known. It is well that this sports area be dedicated to his memory. As the sun rises in the east and leaves us in the west, so it was some 56 years ago Herbert came into the world in the east side of his beloved Fayette County and now we are honoring his memory in this, the western extremity of the county, and, as the sun sets in all its beauty, so he has left to all of us glorious memories of sportsmanship unsurpassed, citizenship at its finest, and a personality as radiant as the noon day sun.

It would, indeed, be superfluous for me to recite to you the many accomplishments of Herbert's in the sports world. Voluminous material has been written and much, much more could be written, but, this afternoon I want to talk about Herbert Parsons, the man, and Herbert Parsons, our friend.

He was born with a quick mind, developed a healthy body, and attained a ready wit; all of which, with his determined efforts carried him to heights in his profession none have equaled or will ever excel. A poem, whose author is unknown, best describes Herbert when he said:

Let me live, oh Mighty Master,

Such a life as men shall know,

Tasting triumph and disaster,

Let me run the gamut over,

Let me fight and love and laugh,

And when I'm beneath the clover

Let this be my epitaph:

Here lies one who took his chances

In the busy world of men;

Battled luck and circumstances

Fought and fell and fought again:

Won sometimes but did no crowing,

Lost sometimes but didn't wail,

Took his beating, but kept going,

Never let his courage fail.

He was fallible and human,

Therefore loved and understood

Both his fellow men and women

Whether good or not so good;

Kept his spirit undiminished,

Never lay down on a friend,

Played the game until it was finished,

Lived a Sportsman to the end.

Herbert wasn't born the world's greatest shot; he made himself the greatest by hard work. This same determination for excellence was carried into other areas of his life. It was in those areas I knew him best because of our very close association.

He was truly an outstanding citizen of this County and the community of Somerville. When asked where he was from, whether he was in the labyrinths of New York City or hunting bears in the wilds of Alaska, he would grin and reply, "I'm from Somerville, Tennessee, half way between Warren and Laconia." More people knew of Somerville because of Herbert than any other dozen citizens of our town. When he would return home from a long, arduous exhibition tour, one of his first acts would be to go around the Square greeting his friends with his customary wit and geniality, always interested in the town he loved and who loved him. How well I remember when little league baseball came to Somerville. No man in town was more enthused and did more during his brief visits home than did Herbert. Those of us who know him so well quite often became amused when he would pass an unkept lawn in town and how vexed he would become.

I knew Herbert as a churchman since we were both officers in the local Presbyterian Church. He worked in the Church with the same enthusiasm he did everything. He was never happier than when he was standing over a washpot of hot grease frying fish or perspiring rivers of sweat cranking an ice cream freezer for an outing of the Men's Bible Class of his Church. How well I remember his vexations over the lethargy of some of the people in the Church.

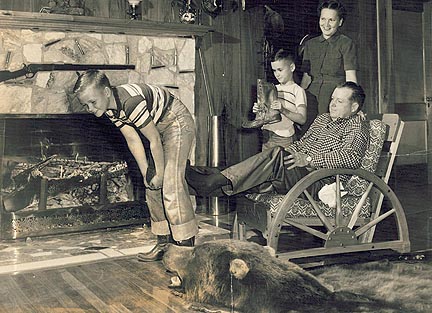

I knew Herbert as a family man. Many times I have heard him say when he would return home how much he missed his family. I don't think he was ever more contented than he was sitting in his customary big chair in his den with a roaring fire on the hearth, surrounded by his family, a few friends, and his many trophies and mementos. When his boys were very young he would express to me his hopes for them, their education and place in life. His concern for his wife and parents was ever foremost in his mind.

The sincere love of family, church, and community is the real criterion of good citizenship, but his contribution to citizenship didn't stop here but was carried over into his work as an exhibition shooter. At each of these exhibitions where there gathered groups of admiring youths who watched his feats with a gun with wishful hope that they, too, might be able to duplicate such wonderful marksmanship, Herbert would turn to the youth and remark that one of the reasons he could shoot as he did was that he never used alcohol or tobacco. Who knows what such a simple truth of clean living has meant to thousands of American youths. Not only were his remarks on citizenship made to youth, but to parents as well. None of his clichés are better known than the classic which touched so many: "If you hunt with your boy, you won't have to hunt for him."

We have all read many tributes to Herbert's memory; and we have heard here this afternoon others so expressive; but to me, I never heard a tribute more beautiful in its sincere simplicity than the one paid him by an old Negro, Uncle George, who had known him all his life and had worked for him for many years. Five years ago last Sunday I stopped by Uncle George's and told him of Herbert's passing; and as he stood overcome with emotion, he looked up at me through a river of tears streaming down his face and said in a choked voice, "Mr. Herbert's gone, he was the best friend I ever had." That remark of simple sincerity of Uncle George's was to me one of the greatest tributes any man can have.

We have all read many tributes to Herbert's memory; and we have heard here this afternoon others so expressive; but to me, I never heard a tribute more beautiful in its sincere simplicity than the one paid him by an old Negro, Uncle George, who had known him all his life and had worked for him for many years. Five years ago last Sunday I stopped by Uncle George's and told him of Herbert's passing; and as he stood overcome with emotion, he looked up at me through a river of tears streaming down his face and said in a choked voice, "Mr. Herbert's gone, he was the best friend I ever had." That remark of simple sincerity of Uncle George's was to me one of the greatest tributes any man can have.

This park we dedicate to the memory of Herbert Parsons will always serve as a reminder of this great man; but so long as hunters thrill at the point of a welltrained bird dog, or sit in a cold wet duck blind, or gather around a camp fire, so long will the feats and life of Herbert be remembered. So long as these majestic trees shall drop their leaves each fall to bud again in the spring, so long will we all remember that broad grin and ready wit. To all of us who knew and loved Herbert, may his memory ever linger in our lives and may we ever recall that our lives are richer because we knew him.

And, now, we dedicate this park to the memory of Herbert Parsons; and as he, for over thirty years, brought so much joy and happiness to so many people, may this park ever serve to bring happiness to all who use it.

“Thoughts About Your Dad”

e-mail from Jack Evans, Delta, British Columbia, Canada, January 13th, 2002

Hello Lynn:

What a nice thought and gesture on your part to take the time to rekindle a flame that has burned very strong within my being for so many years. I first met your dad at the Victoria Gun club located on the outskirts of Victoria, British Columbia where Herb was to put on a shooting exhibition sponsored by Winchester Canada. I was just a very young and enthusiastic farm boy who was dirt poor then. I could not afford expensive store bought ammo for my single shot 22 Cooey rifle, which was made in Canada by Winchester. However, I was fortunate enough to have a friend and neighbor that worked at the military base and was responsible for the maintenance and up keep of the training ranges. He would give me ammo for helping him clean up the ranges and it was this old gentleman that gave me the opportunity to watch and to finally meet your dad.

I was asked if I would clean up all the garbage (in reality the left over targets and spent ammo, which there were tons of). In return, I would get to meet the Winchester Pro who was on tour. I had never heard of him, let alone try and understand why any company would pay someone to shoot all their guns and blow away vast amounts of ammo. Anyway, I was in love with shooting and figured that just maybe I might end up with some more military ammo.

When I first met your dad, I was lost at what he was trying to say as he spoke so fast and everything that he did say was either funny or above my level of intelligence. I was not up to speed on current events or famous sports figures. At one point in the show, Herb asked for someone in the audience to come forward and try the latest high power Winchester 22 rifle by trying to hit a stump some distance off in the horizon. (It was a very small stump) Not one person in this very large audience would step up and try the shot. Herb looked over at me, busy about cleaning up the blown away cabbage, melons, eggs and whatever he had in his shopping cart at the time, and said “Come over here, son”! I will never ever forget that phrase as it was the spark that ignited the burning flame that still burns within my soul to this day.

When I first met your dad, I was lost at what he was trying to say as he spoke so fast and everything that he did say was either funny or above my level of intelligence. I was not up to speed on current events or famous sports figures. At one point in the show, Herb asked for someone in the audience to come forward and try the latest high power Winchester 22 rifle by trying to hit a stump some distance off in the horizon. (It was a very small stump) Not one person in this very large audience would step up and try the shot. Herb looked over at me, busy about cleaning up the blown away cabbage, melons, eggs and whatever he had in his shopping cart at the time, and said “Come over here, son”! I will never ever forget that phrase as it was the spark that ignited the burning flame that still burns within my soul to this day.

When asked if I had ever shot a rifle, my reply was no, only a 22 single shot. “Son”, he said, “that’s a mighty fine rifle”, and when he asked “what make is it?”, all I could think of was Cooey. I was too unsure of any other name or model. “Well now is your lucky day because from now on you will be a Winchester man, after you blow away that there yonder stump with this Winchester auto 22 rifle”.

There I was in front of about 200 sportsmen and media officials standing next to the greatest shooter on earth. At the time, I was not aware of his greatest feats - the ones with his Model 12 shotguns. Herb adjusted the sights on that beautiful little gun, and as he handed it to me he said “Believe in what you can do and it will happen more times than not!” As I touched off that shot some 50 years ago, I will always remember the confidence that he instilled within me, and yes, it’s still with me to this day. I was not aware at the time, but that far off yonder stump was loaded with blasting powder and at the shot, one of Herb’s assistants pushed the plunger down and that stump was gone! “Now that’s a rifle, son, even if it’s only a 22!”

I did get a chance to shoot his Model 12 short barrel skeet gun and was truly amazed at just how smooth the action worked. I was totally blown away when your dad held up a big handful of clay targets, threw them up into the air himself, and yes, broke every one of them before they hit the ground! WOW, I was hooked on Herb Parsons and Winchester.

After the show was over and all the guests were on their way, your dad was still on the grounds talking with others. As I finished my clean up chores, he asked if I had a way home and I answered “Yes, it’s only 4½ miles and I can run it in no time”. “Would you like a ride home and maybe you can show me your Cooey?” he said. I did get a ride home that day and Herb was introduced to my Grandparents who were my guardians as I was from a split home. Your dad put on a private show for us there on the back pasture of our farm with my little 22 Cooey after showing me how to adjust the rifle sights. Those moments are still with me to this very day.

Over these many years I have been fortunate enough to have had the chance in life to help others not only in business, but also in the shooting sports as I spare as much time as possible with youngsters and try to emulate your dear dad’s passion and outlook on life the best that I can. Yes, it really does work, because like they say, the more you give, the more does come home. I still have that old Cooey rifle and cannot even start to count just how many new shooters have got away their first shot on that very special Winchester.

Oh yes, Lynn, in 1975 I did earn a berth on the Canadian Olympic Shooting Team (Shotgun), but was unable to attend due to a very large contract that required my time. But, as I always say, I went for the real Gold and have never looked back.

I owe so much to your Dad, especially the incentive that he instilled within me and I always admired his sense of humor. Even the part I did not understand or could keep up with. He sure could make people feel comfortable without even trying. One shortcoming that is always there when I think of your dad is that I never did find a Model 12 Skeet gun similar to the one he let me shoot so many years ago. When I asked your dad how he got it so smooth when pumped, he said that he spent many hours with it full of fine southern river sand and just kept on ‘a pump’n!

Thanks for giving me this opportunity to relive those cherished moments that took place so many years ago with one of the greatest shots that ever looked down a barrel.

May this new year we are just starting into be one of positive and blessed events in your life and filled with enjoyable and treasured memories that last forever.

All the best Lynn:

Jack

TRIBUTE TO HERB PARSONS

given at INTERNATIONAL RICE FESTIVAL

October 15, 1959

by James W. Barnett

Many people have given of their time and talents to make the International Rice Festival the great success it is, Among these, Herb Parsons, the farm boy from Tennessee, stands well out in front.

Herb first came to us in 1946 when we arranged with Winchester-Western, his employer, for him to give a shooting exhibition here in connection with the Festival's program. That was a fortunate day because he came back year after year at our request, to become the greatest single attraction on our program.

His exhibition drew people each year from miles and miles around, and they packed the golf course by the thousands to see him perform shooting feats of uncanny skill. When he was here the last time he shot seven flying targets, which he threw up, hitting the last just inches from the ground. He was the only person in the world who ever accomplished this. He always said, "If I can shoot six, I can shoot seven". We all expected it would be eight targets this year.

He was a perfectionist, and each year brought new surprises in his performance. He had lots of tricks that were not tricks in the usual sense. Some of them you will remember were: Tossing a metal washer in the air and shooting through the hole in the center with a .22 rifle. When the washer fell unmarked, some doubters figured he had missed.......so for them, he would toss other washers into the air and send them whizzing to the right or left, as they called the shot, with the bullet ricocheting in the other direction. He would drill a quarter for you through the lady's eye or ear as requested.

A favorite trick was to make cole slaw or salad. For salad he expertly placed one shot that would cut the stem off the cabbage so the leaves came fluttering down, ready for dressing.For cole slaw he shredded the cabbage with a shotgun shell so it rained down as from a salad maker.

He proved again and again that a pump gun was as fast as an automatic by breaking six eggs thrown into the air before they could hit the ground.

Herb could shoot his .22, then zip the muzzle around in time to hit the empty as it was ejected from the chamber, sending the empty zooming through the air along with the bullet.

It has been a source of real pride to us that it was the International Rice Festival which first billed Herb as "The World's Finest Marksman".

We knew Herb best for his trick shots. He was just as well known in other quarters for other skills. He ruled the professional division of the Grand American national trap shoot at Vandalia, Ohio, for many years. Year after year he was named to the All American trapshooting team.

Herb was a shooting instructor in the armed forces during World War II and after his discharge he gave shooting exhibitions all over the world. I remember him telling me of a time when he was taken to a top secret station .........somewhere on the polar ice cap. He had no idea where he was, and there was so much snow and ice, he had to give his exhibition on the steps of the mess hall.

The story about the beginnings of his career is interesting. A salesman for Winchester shells was hunting on Herb's father's farm in Tennessee. Herb was just a small boy, but he was shooting quail along with them. There was one difference. The two men were using shotguns. Herb had a .22. He liked hunting so much and used so many shells that his father, as an economy measure, made him use a .22. Another thing.....Herb got the most birds! This first attracted Winchester to him as a possible replacement for the aging Topperwein, their exhibition shooter.

He was only 51 when he died this summer, and he had been a professional shooter with Winchester-Western Arms Co. for 30 years.

His shooting is legendary and will be remembered as long as sportsmen gather.

Herb was without a doubt the greatest marksman of all times. But there was much more to him. Herb enjoyed life to its fullest and gave generously of himself. He had friends all over the world and he never forgot one. When Ernest Meaux brought him a deodorized skunk and a little alligator last year, Herb was touched and commented later, "You know, that boy went to a lot of trouble to get those for me".

We waited eagerly each year for the phone call announcing his arrival...."Hi Neighbor!, you got the coffee ready?"

Herb believed in God and appreciated the wonders of his creation. He knew the woods and the fields and all the game to be found there. He could imitate them. He could call a wild turkey, a crow, a hawk, an owl, a duck, a squirrel and a goose.

He was an officer in his church and did outstanding work with the boys of his community. Through the example he set, he had an influence on the boys of the nation. Can't you hear him saying to the boys who crowded in too close during his shooting exhibition: "Boy, it took a lot of biscuits for your Daddy to raise you that big. I sure wouldn't want anything to happen to you now", and to the fathers, "Hunt WITH your boy and you will never have to hunt FOR him".

Herb was one of the outstanding humorists before the American public. His running line of homespun wit, while doing the most exacting feats of marksmanship, made his show a hit with all people of all ages. We have one lady in Crowley in her 80's who never missed a performance. There is the boy who had to sit on his father's shoulders to see. At Herb's performance here last year, he towered with the big ones in the back row and had cut college classes because he could not miss Herb's show.

Herb had other talents. He won the International Duck Calling Contest here in 1950 and 1951, and the same years he won the National Duck Calling Contest at Stuttgart, Arkansas. He could have kept on winning but retired from competition to give the other fellow a chance at it. His calls have been preserved on records as a model for future duck calling.

Herb had a very particular association with our International Rice Festival. He was our traveling ambassador, a portfolio he took on himself because he was interested in our celebration and all the people here. He performed in every state in the Union and in many foreign countries. And wherever he went he talked of the International Rice Festival, of Crowley, and of the people of South Louisiana. He wore the emblem of the International Duck Calling Championship on his sport coat wherever he went.

It was he who first realized the possibilities of our International Duck Calling Contest and put us in touch with Bill Tanner of Von Lengerke & Antoine in Chicago. Together, they interested sportsmen all over the U.S. in entering our contest and they helped put it over year after year.

I think the greatest tribute he paid us was when he said, partly in jest, but prompted by the love in his heart, that he was going to petition the Louisiana legislature to change his name to Herbert Pousson because he had South Louisiana in his blood.

The International Rice Festival owes much to Herb Parsons. Through his feats of marksmanship he achieved immortality, but we will remember him for his gentle nature, his spontaneous humor, his simple farm boy character, for his love of our people and our reciprocal love for him and our admiration for the high qualities of manhood he personified.

The International Rice Festival extends its sympathy to his widow Oneita Parsons, to his sons Lynn and Jerry, and to his parents of Somerville, Tennessee.

We acknowledge a debt of gratitude to Winchester-Western for the many fine performances Herb put on for us and for the high ideals he held before the people of our area.

A TRIBUTE

by the WEST TENNESSEE SPORTSMEN'S ASSOCIATION

Be It Resolved, that our beloved friend and member, Herbert Parsons, removed from our midst by the hand of Providence on July 19, 1959, is sadly missed by the West Tennessee Sportsmen’s Association;

THAT ALTHOUGH HERB’S SPAN OF LIFE was not great, it was a full and happy life, a useful existence unmarred by petty thought or deed, the life of one of God’s noblemen, who walked close to his Maker throughout his lifelong contact with God’s creation, and his love for his fellowman; a man who appreciated fully, and made use of, the abundant blessings of nature; a rugged man of steadfast heart, who, although he excelled in many fields, and achieved the highest pinnacle of success, remained a man of modest nature; who, though acclaimed throughout the world, and who knew and enjoyed the close association and friendship of celebrities, never lost “the common touch” which impelled him to seek opportunities to promote the sports he loved, and to teach and counsel not only his own beloved sons, Jerry and Lynn, but all boys, in wholesome recreation and an appreciation of the better things of life; the rugged sportsman, who retained the strain of gentleness in his nature, which made him beloved of young and old alike, in all walks of life; the understanding humanitarian, who recognized the needs of others, and traveled to the far corners of the earth to exhibit his talents to the members of our Armed Services, with no thought of reward, except the pleasure of his contribution to the happiness of his fellowman; a man whose daily life bore witness to the practice of his religion and his innate faith in God, and whose greatness lay not in his fame, which was worldwide, and in his splendid accomplishments, but in the simplicity of his nature; that although Herbert Parsons achieved an enviable mark in the world of entertainment, and a record in sports which may never again be equaled by any individual, his fame can never overshadow the staunch goodness of his character, and the simple, down-to-earth qualities of this great soul, who lived his life close to nature, and whose symbol of mortality now rests in the bosom of the good earth he loved.

Be It Further Resolved that this organization, to which Herb Parsons over a long period of years unquestionably made a greater contribution than any single individual, extends heartfelt sympathy to his beloved Oneita and the two fine sons who blessed their marriage; that Herb Parsons, faithful husband and father, and our friend and companion on many happy occasions—the man who sought not fame, but perfection in his undertakings, has gone to the reward to which his way of life entitled him. Rest in the assurance that his freed spirit travels that happy, untrammeled realm, where the terrain is level, the air is crystal-clear, and the birds are ever on the wing.

TIME CANNOT ERASE, nor even dull, the imprint of the good life of our absent friend upon the entire community. His sojourn among us was a never-to-be forgotten blessing, and his memory indeed “a thing of beauty, and a joy forever.”

Respectfully submitted,

West Tennessee Sportsmen’s Assn.

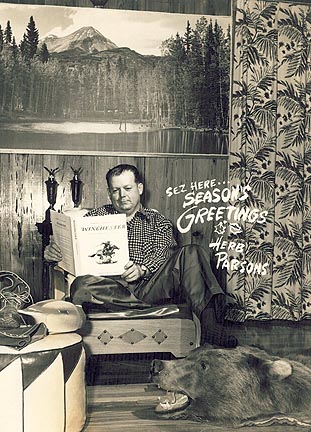

by Dr. Wayne Capooth, THE DOUBLE GUN JOURNAL, Summer 2006

Photography Courtesy of Lynn & Jerry Parsons

The old home is empty now. Cobwebs hang here and there and dust gathers on the mantle. Time was when the home held life, where people came and told a tale and laughter and talk continued on into the night. The pictures on the walls reveal a family of long ago, and the scrapbook longs for the touch of a hand. Thumbing through it, one can hear the report of a shotgun or a duck-call sound, even though there is no one there. The imaginary sounds that fill the rooms are but memories; they will echo through the years. No one can silence them; they are there for everyone to hear.

To this old home, first came Lynn. He was not sure he wanted to share his world with a playmate, for it took him a week to decide if he wanted a brother or a sister after his mother asked him which he wanted. After much deliberation, at the tender age of two and a half, he told her, "I want a brother."

Then came Jerry.

Three years passed, and while Lynn, no taller than his Daisy Red Ryder BB gun, worked the lever, Jerry grasped the muzzle with all his might, holding the stock firmly against the ground. It was all they could do just to cock the "dad-blamed thing"—and another blackbird fell.

Month after month, through the years, every afternoon, from 4 p.m. until dark, they shot a bucket full of BBs, littering the yard with blackbirds and sparrows. They weren't wasted, for the cats took their share and the locals took theirs, making blackbird pies.

While Jerry continued shooting with the Red Ryder, Lynn, now 7, progressed to clay targets, shooting a .410-gauge Winchester Model 42 pump gun. A year later, Lynn and Jerry, along with their mom and dad, loaded into their Winchester-red Pontiac station wagon, with two humongous  Western shells attached to the top, and headed north. Not only were these shells advertisement for Winchester-Western, but they also served as speakers for Herb Parsons' Public Address equipment during exhibitions.

Western shells attached to the top, and headed north. Not only were these shells advertisement for Winchester-Western, but they also served as speakers for Herb Parsons' Public Address equipment during exhibitions.

While Lynn was sitting in the stands with several hundred Boy Scouts in Greenville, Ohio—home of Annie Oakley, his dad paused in the middle of the show to say, "Friends, I want to introduce a boy to you. He's just an ordinary American boy. I say that because it's the truth. But that's not the way I feel about it. I feel he's an extraordinary boy because—because he's my boy."

The pause between the first because and the second because was beautifully timed, and the last words came over with deep feeling enhanced by a Tennessee accent.

Herb used several devices in teaching his boys to shoot. He painted a croquet ball white for a target. He rolled this hard across the ground. When the boys shot, they could see where their shot charges hit the ground and thus learned how much ahead of the ball they must shoot. Another lesson was with clay targets thrown low over a pond. Here again the boys could see where the shot charges went when it didn't break the target. It was only when the boys had learned to lead a moving target that Parsons began throwing clay targets up in the air.

So summer after summer, the boys—and Oneita, their mother—traveled with their father, one year traveling west of the Mississippi and the next, east of the Mississippi. Oftentimes, a highway patrolman pulled them over, curious about the large shells on top of their vehicle. They couldn't travel down the highway without some highway officer pulling them over, just to chat.

On the way to an exhibition, Parsons would stop at a supermarket where he collected what he called his "groceries." He bought oranges, grapefruit, potatoes, cabbages, turnips, and several dozen eggs.

When Jerry was eight, he joined Lynn for the first time in Cheyenne, Wyoming. There he shot a newly released, semi-automatic, 20-gauge Model 50, breaking target after target. When Lynn was a teenager, his dad surprised him during an exhibition at the L.A. Coliseum by loading six shells into his Model 12, 20 gauge. Six targets were thrown into the air and all six spattered. A thunderous applause followed.

Herb Parsons was born on a farm in Fayette County, Tennessee, in 1908. After six summers, ready to start school, he was given his first gun, a single shot, Winchester .22 rifle. He took it and slew himself a bobwhite—on the wing. Then he progressed to the local coal yard, where he regularly turned hand-thrown lumps into black dust. His first limit of quail came at the age of eleven.

While his friends were spending their money chasing girls, Herb tucked his coins away for ammunition. When hunting season was in progress, he stayed in the fields and forests until way past dark.

Every kid wonders what his fate in life will be. His was sealed when as a freshman in high school Herb witnessed a demonstration by Adolph Topperwein, Winchester's great exhibition shooter.

Topperwein was just one of the many exhibition shooters in the olden days. Traveling all over the nation performing exhibitions, establishing reputations as professional marksmen, and serving as good will ambassadors for the companies they represented, these men became legends in their own time.

Herb Parsons Winchester Model 21

In the 1870s, Adams Bogardus, an Illinois market hunter, set the pace by bursting glass balls out of the air. On July 4, 1877, in 75 minutes, he fired one thousand times and missed only 27. Two months later, he tried another thousand; this time, 17 escaped his pellets. Before the year was up, he ran through a third thousand, shattering 990. And the race was on. In less than a decade, exhibition shooters were everywhere.

When the razzle-dazzle of Wild West shows ended, arms and ammunition companies got into the act. They put dozens of top-notch shooters on the road. Winchester hired Topperwein and his wife "Plinky." Remington employed Billy Hill, while Peters hired Dave Flannigan.

Nevertheless, it was Parsons who rose above them all in celebrity status. He possessed a flair for the spectacular, a gift of gab, and he also knew how to put birds on the ground.

Parsons' opportunity came in the early 1930s, when Topperwein's failing vision caused him to look for a successor. Parsons was a natural, and spent a great deal of time with the master, perfecting his own routine. Like Topperwein, Parsons was a stickler for realism. He was an exhibition shooter, not a "trick" shot who performed staged or rigged acts. In addition, he knew the more pizzazz a shooting show had, the more a crowd would love it.

In the 1940s, Parsons gave 238 exhibitions to soldiers at military installations. He served as a shooting instructor teaching aerial gunnery to flight crews during the war. Moreover, when hostilities ceased, he returned to the exhibition circuit for Winchester, putting on thousands of exhibitions, touring every state in the nation plus Cuba and Canada. In his performances, he used 16 guns in 52 different ways.

His admirers, and their number was legion, claimed he easily outdid all the feats of Bogardus, Carver, Annie Oakley, Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild West Pawnee Bill, and the other famous shooters, not only owing to his brilliant gun pointing but because he was truly a showman-shooter.

He would toss seven clay targets into the air at once and shatter every one of them before any hit the ground. He remarked, "The hard part is not the shooting but the tossing of the seven targets so they spread well apart." He fretted every time he broke two with one shot and felt as though he cheated the audience.

He would suspend a can of gasoline over a candle inside a 55-gallon barrel, then render the whole works to a towering inferno from a safe distance. Using a mirror and two rifles, he would break two targets at the same instant–one in front, the other directly behind him. He could take five eggs in his hand, lay his gun on the ground, then throw the eggs behind him, rise, and shoot all five eggs.

Throwing a washer into the air, he said he would hit it so it would go to the right. It did. Then he said the next one would go to the left. It did. The only trick was to shoot at one side of the washer—on the left to make it go to the right, on the right to make it go to the left.

During his shows, he went quail hunting with "radar" ammunition—so he said. "The advantage of radar ammunition was that you can't miss. Radar directs the gun to the target."

Parsons would walk along throwing eggs and shooting from the hip. He seemed infallible but finally—on purpose—he would miss one. He'd say, "That was a hen quail—the radar only works on rooster quail." With that he would throw another egg and smash it. "You see," he said, "that was a rooster quail." As a grand finale, Parsons would explode a jug of gasoline with the last shot of the show.

Parsons became friends with stars of the era. He shot trap with Clark Gable and Roy Rogers, hunted ducks with Wallace Berry and Andy Devine, and did the trick shooting for the movie Winchester '73, starring Jimmy Stewart.

Olin Mathieson, of the Winchester Arms Company, could not anywhere near fill the requests for his appearance. Young and old, novice gunner and veteran alike, all enjoyed a Herb Parsons' performance. At the height of his career, Winchester was booking him three years in advance, paying him a thousand dollars a month.

Herb performed before more people than any exhibition shooter in history. He starred in a color film, Showman Shooter, which was seen by over 30 million.

Nevertheless, no matter how high his star rose, he never forgot his roots. When asked where he was from, whether he was on Fifth Avenue of New York City or hunting bears in Alaska, he would grin and reply, "I'm from Somerville, Tennessee, halfway between Warren and Laconia.

He was a regular attraction at the World's Championship Duck Calling Contest during the early 1950s. He won it in 1950 and 1951, adding the International Duck Calling Crown at Crowley, Louisiana, in 1949 and 1950. Herb was later a judge of these contests. He also held shooting exhibitions at the Stuttgart High School football field for Winchester during the World Duck Calling Championships.

During one of the championships at Stuttgart, the family stayed on the third floor of the Riceland Hotel, as they usually did. Jerry, Lynn, and one of their friends, Marion McCollum of Stuttgart, got a little mischievous. Jerry had gotten in the good graces of the elevator operator who allowed him to take control. One night, the kids decided they would throw some fireworks out the window and then quickly head down the elevator to the first floor. As soon as Jerry opened the elevator door, Herb and Oneita greeted them with "Let's hear your story."

Jerry, stammering with each word, went first and took the blame for opening the window, turning off the lights, unwrapping the paper on the fire crackers, and operating the elevator. Marion, squirming, admitted to throwing the firecrackers. After all this guilt was expressed, Lynn thought he was home free, so he puffed up his chest and blurted out, "I just lit them."

Not all of Herb's shooting was done for display, either. He was also quite competitive on the trap range. In 1954, he won the professional division at the Grand American Trap Shoot, and from 1949 through 1958, he was a member of Sports Afield's trap and skeet all-American team. He shot a Winchester Model 21 double-barrel, while most trapshooters of the time were using single-barrel guns or over-and-unders. When asked if he found the side by side a disadvantage, he always answered, "No sir."

He was inducted posthumously into the Trapshooting Hall of Fame at Vandalia, Ohio, and is an enshrinee of the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame and the Tennessee State Trapshooting Association Hall of Fame.

Herb loved to hunt; it came naturally. His trophies included near-record Alaskan brown and black bears, moose, antelope, and many white-tailed and mule deer. Nonetheless, quail and waterfowl were his true loves. When hunting with Jerry and Lynn at their farm near Somerville, they hunted on horses with five ranging pointers. It was the boys' responsibility to flush the birds, once the dogs had pointed and backed, while Herb remained in the saddle and did his shooting. Oftentimes, three birds were dropped from a covey rise. The boys also dropped a few.

Moreover, his skills doubled in the duck blind. A paddler once remarked, "Ah never seen a man who could shoot like dat. Dat man was a machine. He never missed. After de hunt, he'd start throwin' things in de air. Little balls and eggs and stuff lak dat. He would toss up a cabbage, den he would look over his shoulder and ask how you wanted your slaw chopped. 'Fore it hit de ground, he'd grind it to bits."

However, every once in a while he could miss. The day after he won the World's Duck Calling Championship in 1951, he went duck hunting with Captain Charles Hopkins, the head man from Winchester. Hopkins had the champion caller and champion shooter with him. How could he fail?

There was a stiff north wind, and the ducks were hedge-hopping down through the snags. Parsons shot a box of shells, killing just two

ducks. He was good but he could miss.

It was Hopkins that hired Parsons, and he often said, "And this Tennessee boy is not only the best shot of them all, but he has real talent as a showman, a sense of timing with his lines as well as with his guns."

Because of his friendship with Reuben Scott of Grand Junction, Tennessee, secretary of the National Field Trial Champion Association, Herb gave several exhibitions at the Ames Plantation, and there was no doubt that the dazzling display of his skill was one of the main highlights of the respective meet.

Herb, during the course of his career, had three 12-gauge Winchester Model 12s, which Winchester nickel plated for him; otherwise they were just like any other Model 12, not altered in any way. As each had bird's-eye maple wood, he called them "Mae West," because they were "blonde and have such beautiful features about the forearm."

The original "Mae West" is on exhibit at the Cody Firearms Museum, in Cody, Wyoming. His Model 21, 12-gauge trap gun, is at the Ducks Unlimited Headquarters, in Memphis.

Some of Herb's happiest moments were when he had a large group of admiring youths sitting around the shooting circle. Watching his feats with a gun with wishful hope that they could do the same, he would then tell them how important it was to get a good education and to be an expert in whatever they did. He told them to try hard to get to the top of the class, to be a good citizen and a leader in their school, work, or play. He told them the reason he could shoot the way he did was that he never used alcohol or tobacco.

Some of Herb's happiest moments were when he had a large group of admiring youths sitting around the shooting circle. Watching his feats with a gun with wishful hope that they could do the same, he would then tell them how important it was to get a good education and to be an expert in whatever they did. He told them to try hard to get to the top of the class, to be a good citizen and a leader in their school, work, or play. He told them the reason he could shoot the way he did was that he never used alcohol or tobacco.

And Herb didn't let a chance go by without taking a gig at his competition to his young audience. He would say, "Now you boys and girls wouldn't eat an apple before it was red and ripe. So never use those green Remington shotgun shells. Let 'em ripen ... SHOOT WINCHESTER. Know your guns and know your ammunition."

Time came when Herb weakened and fell at the age of 51. His mate, who helped him carry the banner high, was left to tarry forth, but Oneita too had an appointment with our Maker, as we all do.

Through his feats of marksmanship, he achieved immortality, but most remember him for his gentle nature, his spontaneous humor, his simple farm boy character, for his love of people, and for the love of his family.

When he left his boys during the school year, he always expressed his hopes for them, their education and place in life. His concerns for his wife, parents, and sons were ever foremost in his mind. He always returned home and told his boys how much he missed them, and he was never any more con tented than when he was sitting in his easy chair in the den with a roaring fire on the hearth, surrounded by his family, a few friends, and his many trophies and mementos.

When he left his boys during the school year, he always expressed his hopes for them, their education and place in life. His concerns for his wife, parents, and sons were ever foremost in his mind. He always returned home and told his boys how much he missed them, and he was never any more con tented than when he was sitting in his easy chair in the den with a roaring fire on the hearth, surrounded by his family, a few friends, and his many trophies and mementos.

At the end, just after his operation, the last words spoken to his boys, while still in the hospital, were, "I've had this operation so I can be well and we can hunt together again."

To me, he is best remembered as the man who coined the phrase, "Go hunting with your boy today and you won't have to hunt for him tomorrow," and he practiced what he preached with sons Lynn and Jerry.

Many tributes were paid the showman shooter, but none more so than the one paid to him by an old Negro, Uncle George, who had known him all his life and had worked for him for many years. Through tears streaming down his face, he said in a choked voice, "Mr. Herbert's gone; he was the best friend I ever had."

A good friend lamented, "So long as hunters thrill at the point of a well-trained bird dog, or sit in a cold wet duck blind, or gather around a campfire, so long will the feats and life of Herbert be remembered. So long as these majestic trees shall drop their leaves each fall to bud again in the spring, so long will we all remember that broad grin and ready wit. To all of us who knew and loved Herbert may his memory ever linger in our lives and may we ever recall that our lives are richer because we knew him."

Nash Buckingham celebrated his death by the following:

"Although Herb's span of life was not great, it was a full and happy life, a useful existence unmarred by petty thought or deed, the life of one of God's noble men, who walked close to his  Maker throughout his lifelong contact with God's creation, and his love for his fellow man; a man who appreciated fully, and made use of, the abundant blessings of nature; a rugged man of steadfast heart, who, although he excelled in many fields and achieved the highest pinnacle of success, remained a man of modest nature; who, though acclaimed throughout the world, and who knew and enjoyed the close association and friendship of celebrities, never lost 'the common touch,' which impelled him to seek opportunities to promote the sport he loved, and to teach and counsel not only his own beloved sons, Jerry and Lynn, but all boys, in wholesome recreation and an appreciation of the better things of life; the rugged sportsman, who retained the strain of gentleness in his nature, which made him beloved of young and old alike, in all walks of life. The understanding humanitarian, who recognized the needs of others, and traveled to the four corners of the earth to exhibit his talents to the members of our Armed Services, with no thought of reward, except the pleasure of his contribution to the happiness of his fellow man; a man whose daily life bore witness to the practice of his religion and his innate faith in God, and whose greatness lay not in his fame, which was world wide, and in his splendid accomplishments, but in the simplicity of his nature. Although Herbert Parsons achieved an enviable mark in the world of entertainment, and a record in sports which may never again be equaled by any individual, his fame can never overshadow the staunch goodness of his character, and the simple, down-to-earth qualities of this great soul, who lived his life close to nature, and whose symbol of mortality now rests in the bosom of the good earth he loved.

Maker throughout his lifelong contact with God's creation, and his love for his fellow man; a man who appreciated fully, and made use of, the abundant blessings of nature; a rugged man of steadfast heart, who, although he excelled in many fields and achieved the highest pinnacle of success, remained a man of modest nature; who, though acclaimed throughout the world, and who knew and enjoyed the close association and friendship of celebrities, never lost 'the common touch,' which impelled him to seek opportunities to promote the sport he loved, and to teach and counsel not only his own beloved sons, Jerry and Lynn, but all boys, in wholesome recreation and an appreciation of the better things of life; the rugged sportsman, who retained the strain of gentleness in his nature, which made him beloved of young and old alike, in all walks of life. The understanding humanitarian, who recognized the needs of others, and traveled to the four corners of the earth to exhibit his talents to the members of our Armed Services, with no thought of reward, except the pleasure of his contribution to the happiness of his fellow man; a man whose daily life bore witness to the practice of his religion and his innate faith in God, and whose greatness lay not in his fame, which was world wide, and in his splendid accomplishments, but in the simplicity of his nature. Although Herbert Parsons achieved an enviable mark in the world of entertainment, and a record in sports which may never again be equaled by any individual, his fame can never overshadow the staunch goodness of his character, and the simple, down-to-earth qualities of this great soul, who lived his life close to nature, and whose symbol of mortality now rests in the bosom of the good earth he loved.

"That Herb Parsons, faithful husband and father, and our friend and companion on many happy occasions, the man who sought not fame but perfection in his undertakings, has gone to the reward to which his way of life entitled him. Rest in the assurance that his freed spirit travels that happy, untrammeled realm, where the terrain is level, the air is crystal-clear, and the birds are ever on the wing.

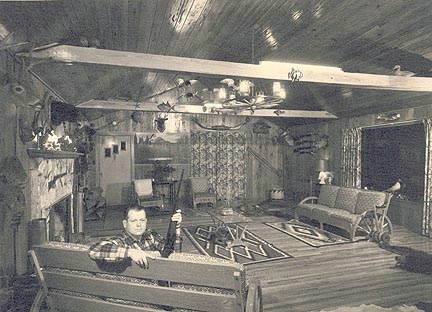

Parsons' house leaves the visitor with no doubt of what he liked. As you go in you face eight or ten mallard ducks "flying" from the ceiling. There is a pair of Winchester '73 rifles, nickel-plated, over the fireplace. Another, a rusted relic, is embedded in the stonework of the fireplace. One of the rugs is the skin of an oversized Kodiak bear that Parsons shot in Alaska. And all about are mementos of a busy life.

"Time cannot erase, nor even dull, the imprint of the good life of our absent friend upon the entire community. His sojourn among us was a never-to be forgotten blessing, and his memory indeed 'a thing of beauty and a joy forever."

Wherever Herb is in heaven, I know he is surrounded by angels sitting around the shooting circle watching and listening. He left something of value on this earth and the world is a better place for his having been here.

Wherever Herb is in heaven, I know he is surrounded by angels sitting around the shooting circle watching and listening. He left something of value on this earth and the world is a better place for his having been here.

As I close the door of the old home, the voices are still, and those who gave us the memories are gone, replaced by a younger generation who dance to the beat of another drummer. Now it's their turn to make their mark in life.

As years pass by, I will cherish the memories the old home gave me, for they will linger on, never to die. I only wish that time stood still.

Scanned courtesy of Wilbur Watje

"A video tour of Herb Parsons' Den of Mementoes,

narrated by his wife, Oneita"

by Lucian Cary, TRUE Magazine, July 1954

Click here for a photo gallery

Herb Parsons can toss seven clay targets into the air at once and shoot every one of them before any hit the ground. But there's a lot more to being a successful exhibition shooter than just knowing how to handle a gun

Herb Parsons, who does exhibition shooting all over the country for Winchester and Western Cartridge, is as well known for his patter as for his shooting. He will talk for fifty five minutes with only one pause of a few seconds while firing up to 700 shots with eight or ten different guns. What he says varies from an earnest plea to keep our country strong and great to the most outrageous corn.

An executive of a competing arms company said to me,"That guy is just too brash." Then he grinned and added, "I guess I wouldn't think so if he were shooting for us."

I was as much interested in how Parsons works as in his shooting. When you come to think of it, putting on an exhibition of shooting isn't too simple no matter how good a shot you are. Parsons said he thought Ad Topperwein, now retired, was the best all time shot among exhibition shooters. But he thought some of Topperwein's routines were too slow. One of these, copied by many other exhibition shooters, was to draw the profile of an Indian or a public character on a sheet of tin with a succession of .22 bullets. This, Parsons thinks, takes too much time. He wants his show to move.

We went to Jacksonville, Florida, where he was putting on a show in the middle of a trapshoot lasting several days at the Jacksonville Gun Club. Parsons has a station wagon in which he travels with his equipment. On the way to the gun club we stopped at a supermarket where Parsons wanted to collect what he called his "groceries." He bought oranges, grapefruit, potatoes, a couple of small cabbages, a turnip and several dozen eggs.

The trapshoot suffered from the weather, which was cold for Jacksonville, from the wind, which made the clay targets do unexpected things, and from trap trouble which caused delays. Parsons had his equipment set up hours before the last squad of the day had shot.

His station wagon is pretty well filled aft of the front seat with a big plywood box. When Parsons let the tailgate down and the lid of the box, I saw pigeonholes containing some sixteen different guns. The pigeonholes were lined with sheepskin, the wool on. Each compartment was marked with the model number of the gun that went into it. Thus the weapons rode well and yet were quickly available. Another compartment held three metal bridge tables. Put together they made one table 71/2 feet long. The dark blue table cover was ornamented with the names of Winchester and Western in red. There was room for ammunition and several kinds of targets, including washers, marbles, clay balls about the size of golf balls and made of the same material as the clay targets used on trap and skeet fields, and small wood cubes.

Parsons set up a pair of steel poles with a rope connecting them. In the middle of the rope he fastened what looked like two clay targets taped back to back. I hadn't the faintest idea what this was for. Another gadget he set up looked like a piece of iron pipe a foot and a half long and an inch and a half in diameter. I didn't know what that was for either. He had a dozen or more empty quart oil cans that he had filled with water. He set these up in a row. And between the oil cans he set clay targets on edge in the grass. He loaded a number of 10 shot magazines for a Winchester Model 63 self loading rifle. Finally he checked his loud speaker. When working he uses a lapel mike. Thus he can talk to a large crowd without raising his voice.

Earl Cramor, a Western Winchester representative in Florida and Georgia, helped Parsons set up shop and stood by for the show. Parsons likes to have an assistant to keep the crowd at a safe distance. He doesn't want small boys to pick up the guns he has laid out on the long table ready for use.

Parsons opened the show with the Winchester Model 63 self loading .22. He told the crowd what the rifle was and began shooting at things he tossed in the air. His first targets were small cubes of wood. Usually these split when they were hit. When a cube didn't split but merely jumped ahead at the shot Parsons hit it again with a second shot. He tossed up washers, marbles and the clay balls shooting fast and talking as he shot.

Then he picked up a .30-30 and began tossing oranges in the air. He changed guns so often that I had trouble keeping track of which gun he was shooting. He had a .22 Hornet, and a .348 lever action rifle among others. He always used a rifle powerful enough to explode an orange or a grapefruit into a cloud of juice, or turn a cabbage into coleslaw. When he shot at the cans of water they virtually exploded. He picked up a Winchester .351 self loading rifle with a 10 shot clip and, shooting from the hip, broke the clay targets standing on edge with great speed.

He shot fast and talked fast though apparently without effort. Bullets flew out of his rifles and words out of his mouth in a steady stream. He picked up three clay targets, put them together in a pile, tossed them high in the air and broke them with three quick shots from a pump shotgun. He said to the crowd that if he could break three he should be able to break one more.

He tossed up four and broke them. He said he really ought to break five. He did. He tried six and broke them. Then he said if he could break six he should be able to break seven. He did.

This last feat is difficult because of the speed necessary. The shots follow each other faster with the pump gun than they would with a semiautomatic shotgun. Occasionally a shot will break more than one target which isn't what Parsons wants. It is difficult to toss up the targets so they spread well apart.

It turned out that the piece of red pipe was a mortar. Earl Cramor fired it when Parsons gave him the signal. Bombs burst high in the air and out floated a black cloth that sailed on the wind. Parsons shot a series of .30-06 traces bullets at it. The spectators could see the bright red sparks of the tracers going through the cloth.

Parsons made his final shot at the clay target, or pair of clay targets, hanging in the middle of the rope connecting the two steel poles. When the shot struck, out came a small American flag. Parsons said a few earnest words about keeping our country strong and great and the show was over. I noticed that he was sweating a little in spite of the chill in the air. He'd been working hard.

Parsons was putting on his show at Ocala, Florida, two days later. I wanted to see it again, since it is never the same twice. Besides, Parsons said we'd get some crow shooting on the drive of 90 or 100 miles from Jacksonville to Ocala. Parsons has twice won the national duck-calling contest at Stuttgart Arkansas, and an international contest as well. He also knows how to call crows. He has made phonograph records of both his duck calling and his crow calling that anyone interested in either should have.

We started out for Ocala at a reasonable hour maybe around 8:30 in the morning. As soon as we got well out of Jacksonville on the main highway, Parsons began using his crow call in connection with the loudspeaker. After a few minutes he said, "Look back." I looked back and was astonished to see five crows following the car down the cement highway.

Parsons stopped the car alongside the road and we went into a patch of pine woods and palmettos. He picked a place where we were pretty well covered with an open space in front of us. He told me to have my gun ready so I would move it as little as possible when I shot. Then he began calling. He called persistently for maybe five minutes. I thought it was no soap and relaxed my attention just as Parsons shot. I saw the crow only as it was falling to his gun. Parsons had shot the leader, or lookout, which it is well to do if you are going to get more crows. If you miss the leader he's going to warn the rest. As it was, more crows came in. Parsons shot four more crows. Between watching him and my natural slowness I shot only one.

I was a bit handicapped by shooting a 20 gauge Browning over-and-under bored for skeet while Parsons was shooting a new Winchester Model 12 in 12 gauge. My Browning is fine for a crow coming in under 30 yards. But it's too open bored to be reliable beyond 35 yards. However, the real difference was in the quickness with which Parsons sighted a crow and his shooting skill.

We stopped off half a dozen times on our way to Ocala. Parsons insisted on going ahead of me and asked me to follow in his tracks. He said we were in rattlesnake country and he was more likely to see a snake than I was. I appreciated his thoughtfulness more after he took me to Silver Springs, where Ross Allen keeps his snakes. There I saw rattlesnakes strike. Parsons said my eyes bugged out so he could have hung his hat on them. I was immensely curious. I wanted to see just how a rattlesnake does it. Those I saw were coiled but a foot or so of the snake's body behind his, head was in an S curve. The keeper held out a toy balloon tied to a stick. It was cold and the snakes were torpid. I saw two of them miss, going under the balloon. But finally one snake got mad enough, his rattles buzzing, for no fooling. I don't know that he struck any faster than a good lightweight delivering a left jab. But he was fast. And the balloon exploded as his fangs hit it. I guess it's a sound idea to wear snakeproof hoots or leggin's when hunting in Florida, rather than sneakers.

On one occasion Parsons killed a hawk and half a dozen crows set up cries of triumph as the hawk fell. Parsons likes to use a hawk call occasionally while calling crows because crows regard hawks as mortal enemies and want to gang tip on them. According to my score Parsons killed thirty-two crows with thirty-five shells. He missed two crows and once he had to fire a second shot at a crow that was hard hit but somehow managing to stay up there for the moment. I avoided counting my misses. But I killed only eight crows.

Parsons had to do a radio interview at Ocala the next clay. I listened in the control room. The interviewer had a few notes but there was no script for the half hour. Parsons talked easily and freely. I felt that the interview had a reality that is often lacking in a prepared radio program. Parsons answered questions about guns and demonstrated his crow, duck and hawk calls. Afterward the head of the station said to me, "That was a radioman's dream of how it should he done."

Click here to listen to the interview.

It rained so hard that day that Parsons thought he couldn't put on his show. However, he picked up six or eight sticks of dynamite and his usual supply of groceries. He put the dynamite on the floor of the car, saying, "If that goes off I'm glad I met you." Actually there was no danger. You have to hit dynamite pretty hard to explode it.

The rain let up in the afternoon and we drove out to a skeet field where, considering the weather, there was a good crowd waiting. Parsons, who was born in Tennessee, put the Tennessee Waltz on the phonograph while he set up shop. He did one thing I hadn't seen him do before. He tied an egg carton to a post maybe 75 yards out. I didn't know what this was for and he was so busy I didn't ask him.

He did many of the same stunts he had done at Jacksonville, with variations. At one point, shooting at washers he threw in the air with a .22, he said he would hit one so it fell near the high house of the skeet field. It did. Then he said the next one would go near the low house. It did. The only trick was to shoot at one side of the washer on the left to make it go to the right, on the right to make it go to the left.

Parsons laid a shotgun on a box. Then, bending over in the position of a football center about to snap the ball. he threw two eggs between his legs and behind him, picked up the gun, turned and smashed them both with two quick shots. He did the same with three eggs.

After that he went quail shooting with "radar" ammunition so he said. The advantage of radar ammunition is that you can't miss. Radar directs the gun to the target. Parsons walked along throwing eggs and shooting from the hip. He seemed infallible but finally on purpose he missed one. He said, "That was a hen quail the radar only works on cock quail." With that he threw another egg and smashed it. "You see," he said, "that was a cock quail."

Toward the end he picked up a .270 and a Weaver scope sight.

He said, "You see that carton of eggs out there. If I don't cut the string that holds it to the post in three shots I'm going to give a boy a rifle."

Parsons took rather deliberate aim at the egg carton. When he fired there was a good healthy explosion as egg carton and post disappeared. I knew' then what he had done with those sticks of dynamite he had picked up earlier.

He said, "That was a .270 Silvertip bullet. You see what it did."

No one was fooled by this transparent exaggeration but the crowd liked it.

Except for filling an egg carton with dynamite or pretending that he is shooting radar ammunition, there is no trickery in the shooting Parsons does. Many years ago I saw Buffalo Bill riding a loping horse around a circus ring and casually breaking glass balls thrown by an assistant with what looked like a Winchester lever action rifle. He was using ammunition loaded with fine shot rather than with bullets. He may have felt that the fine shot wouldn't carry far enough to hurt anybody in the audience or, being less than good with a rifle, that he could put on a better show.

Parsons, whose audience is usually composed of shooters, doesn't use shot cartridges in rifles. He doesn't need to and he couldn't do some of his stunts with shot cartridges such as the one where he tells in advance which way he is going to drive a washer with a bullet. He told me that it would be possible to put on a good stage show while firing nothing but blanks. This reminded me of a familiar story--the one about the vaudeville assistant who was asked what he did. He said, "I'm the guy who blows out the candle when the boss shoots at the wick."

What Parsons does is properly exhibition shooting rather than trick shooting. The only malarkey is in his patter not in his shooting. Except for the Model 70 .270 with a scope sight his rifles arc standard factory models, with factory open sights. The stocks of his shotguns are slightly modified so they fit him. He showed me a trick he uses when they aren't. He raises the comb by putting a strip of moleskin adhesive plaster on it. There are commercial pads made to lace on and raise the comb of a gun. The trouble is they also increase the thickness, pushing the cheek of a right-handed man too far to the left and vice versa. The moleskin is better. You can use two or more thicknesses on top of the comb if you need to.

Parsons and his wife and his two sons live in Somerville, Tennessee, 40 miles or so from Memphis, in a house that leaves the visitor in no doubt of what Parsons likes. In common with many men of vigor with good appetites he is trying to hold his weight down though the meals served in his home are against him. The night I had dinner with the family the main dish was wild duck. But there was roast coon too, and I don't know how many other things besides lima beans. mashed potatoes, a salad, pickled peaches, corn bread and strawberry shortcake.

The big living room, which Parsons calls a den, has a ceiling that roes tip to the roof and is lined with pecky cypress. As you go in you face eight or ten mallard ducks "flying" from near the roof the way they do when they are coming in to decoys. There is a pair of Winchester 1873 rifles, highly finished, over the fireplace. Another, a rusted relic. is embedded in the stonework. One of the rugs is the skin of an oversize Kodiak bear that Parsons shot in Alaska. And all about are mementos of a busy life.

Parsons has been teaching his sons, Jerry, aged 7, and Lynn, aged 11. to shoot. He has no intention of bringing either of them up to become exhibition shooters. He wants them to choose for themselves. But he wants them to know how to shoot. Last summer. Lynn Parsons, then 10 years old, spent some weeks touring with his father and doing some exhibition shooting. He wasn't big enough to shuck a Model 12 Winchester but he could shoot a .410.

I wasn't there but this is what I heard about the way Herb Parsons introduced Lynn Parsons. The boy, dressed in a white shirt and white shorts, was sitting in the stand with several hundred Boy Scouts. Parsons paused in the middle of his show to say, "Friends, I want to introduce a boy to you."

This was Lynn's signal to start down out of the stand and join his father. Parsons went on, "He's just an ordinary American boy. I say that because it's the truth. But that's not the way I feel about it. I feel he's an extraordinary boy because he's my boy."

They tell me that the pause between the first because and the second because was beautifully timed and the last words came over with deep feeling, enhanced by a Tennessee accent.

What the boy did after his father had introduced him was to break clay targets thrown in the air one at a time, two at a time, three at a time, four at a time. He did it as calmly as if he were back home on the farm where his father had taught him to shoot at moving targets.

Herb Parsons used several devices in teaching his son to shoot. He painted a croquet ball white for a target. He rolled this hard across the ground. When the boy shot he could see where his shot charge hit the ground and thus learn how much ahead of the ball he must shoot. Another lesson was with clay targets thrown low over a pond. Here again the boy could see where the shot charge went when it didn't break the target. It was only when the boy had learned to lead a moving target that Parsons began throwing clay targets up in the air.

Parsons gave me a lesson in shooting at targets thrown in the air. He is ever so skillful at throwing. He throws targets so you see the whole target and not just the edge as in skeet and trapshooting. A pair looked easy. But I did not find it so. For one thing. the range was short where the pattern of the gun has not opened up. For another, leading a falling target is tougher than leading a rising or crossing target. I do not know of any harder shot in the field than one where a bird is going down fast.

I tended to shoot under falling targets so much so that Parsons checked my gun and tried it himself. There was nothing the matter with the gun fit. The trouble was in me.

I asked Parsons how he did a shot I had seen him do in his show. When he was pretending to be shooting quail with radar ammunition he threw one egg high in the air, looked around at the crowd as if he didn't know where it was, turned as it was falling straight down. and broke it.

I asked how he did this, since passing the falling egg with the muzzle of his gun would hide it.

Parsons said, "I don't follow it straight down and pass it. I slice it. I start my swing from one side and conic down and across at an angle. That way I can see it all the time."