On April 3, 1948, at Storm Lake – the heart of northwest Iowa’s duck country and an old stronghold of fine retrieving dogs – a litter of eight black Labrador Retriever pups was whelped.

On April 3, 1948, at Storm Lake – the heart of northwest Iowa’s duck country and an old stronghold of fine retrieving dogs – a litter of eight black Labrador Retriever pups was whelped.

The sire was Timothy of Arden, owned by Ed Quinn of Storm Lake. The dam, Alta of Banchory, was owned by the late Merle Cadwell of nearby Alta. There were five males and three females in the litter and they were born in good season, for by the time they were weaned and their obedience work begun it was early June and the entire summer lay ahead.

Quinn managed the pups’ first training, and summer suited his purpose. He took advantage of a blazing July to introduce the puppies to water, working them in a spring-filled gravel pit several times a week, usually in the cool of evening. They went for water as only young Labs can, and although none was outstanding all showed early promise as good gun dogs.

Neither Cadwell nor Quinn kept any of the pups. All were sold in early fall when they were about six months old. At least two of the females stayed in Iowa. One male, Black of Bunham, went to George Holmes of Lincoln, Nebraska. An Iowan, George Wells of Sioux City, bought another of the males and Merle Sternhagen of Washington State bought the pick of the litter – a male puppy he named “Gin”. The two remaining male pups were sold to E. J. Karnes and Robert Howard of Omaha for $50 each. In Quinn’s opinion, Karnes made the better buy – a sturdy little black male that was “a better retriever as a puppy, and superior to Howard’s pup in nearly every way.”

Both young Labs were shipped to Council Bluffs where they were delivered to their new owners and taken to a well-known Omaha kennel for a few days. Quinn stoutly maintains that the two puppies were immunized for rabies, hepatitis and distemper before leaving Storm Lake, but within a few days after their arrival in Omaha both developed acute symptoms of distemper. Karnes’ pup was taken to a veterinarian, where it died. Howard too his puppy home and placed it in a basket by the basement furnace.

The little retriever showed no improvement and Howard was advised several times to have him disposed of. For nearly a month the pup was as sick as an animal can be and remain living. When the owner went into the basement in morning or evening the puppy was too weak to stand, and no one could understand how he stayed alive.

Mrs. Howard tended the puppy almost constantly, making certain he was warm and even managing to feed him an occasional egg. For weeks the small Labrador clung to life with a remarkable persistence: he did not seem to grow stronger, nor did he appear to be failing. He was simply holding the line in a desperate battle.

But Mrs. Howard’s loving attention and devotion to the sick puppy finally turned the battle.

“One night I went downstairs to have a look at him,” Howard says, “and he managed to stand in his basket and greet me. I knew then that he was going to make it.”

Soon after this, with the puppy on the mend and able to take light exercise, Howard named him.

The trainer had owned several dogs named “Buck” and liked “the yell of it,” for it was an easily-heard call name. Acting on the optimistic hunch that the convalescing puppy might someday rank high in his class, Howard named him “King Buck.” At the time, it was simply a hopeful idea. No one could know it was a prophecy.

But the effects of distemper weren’t shaken off overnight. King Buck did not eat well and was very thin. When Howard took the young dog to a veterinarian, he was told that Buck had a bad heart and should not be run in the field. As if this weren’t bad enough, the dog’s stools were sometimes bloody and Howard feared that his Lab might have suffered internal damage. Yet, Buck ran well. Even more important, he seemed to want to run. And by the time he was eighteen months old, his weight and appetite began to gain and Howard never noticed symptoms of poor health again.

In his second autumn the dog began his first real field hunting. He was not a good trailer of crippled pheasants, but he was rock-solid under the gun even though Howard didn’t require him to be steady to shot in the field.

“One day I shot a pheasant and ran after it,” Howard recalls. “After about twenty-five yards I realized that I was alone, and looked back to see Buck still standing there. I yelled: ‘Well come on!’, and he did. He never held tight on field pheasants again, but still refused to break shot at field trials, He seemed to know when and where to hold steady; he’d hold at field trials but break on pheasants during a hunt. A real brainy dog. Buck was also eager and affectionate with me and showed no inclination of being shy or a one-man dog. He didn’t suddenly ‘come of age’ as some dogs do. In fact, he won a licensed derby when he was only eighteen months old.”

That particular derby may have been Buck’s first licensed field trail. The young dog also won first place in September, 1949, at the Missouri Valley Hunt Club’s licensed trial in Iowa.

Buck tallied some impressive early victories, but in spite of his growing experience and polish he still had bad days. There were times when he marked so poorly that Howard suspected poor eye-sight, and remembered that bout of distemper with concern. But Buck continued to improve and placed in several more derbies. He was strong in water and was an honest dog that worked to capacity.

By this time, Howard sensed a quality of greatness in the young Labrador- a strange spark that was fanning brighter with each field trial. Yet, he made a puzzling decision and asked Byron “Bing” Grunwald of Omaha to buy the dog. Howard says today that it was a growing knowledge of Buck’s potential that caused him to sell, for the trainer felt that he couldn’t afford to run his retriever in top-flight trails and give Buck a real chance to prove himself. King Buck was sold to Grunwald for $500, with the stipulation that Howard could continue to train the Labrador and handle him in trials.

By this time, Howard sensed a quality of greatness in the young Labrador- a strange spark that was fanning brighter with each field trial. Yet, he made a puzzling decision and asked Byron “Bing” Grunwald of Omaha to buy the dog. Howard says today that it was a growing knowledge of Buck’s potential that caused him to sell, for the trainer felt that he couldn’t afford to run his retriever in top-flight trails and give Buck a real chance to prove himself. King Buck was sold to Grunwald for $500, with the stipulation that Howard could continue to train the Labrador and handle him in trials.

He still had wild days, however, and fooled some of the experts. Just after Buck’s third birthday he was running in an open all-age stake at Lincoln. A triple-mark retrieve was set up and Buck tore over most of the field for each bird he picked up. After the trial one of the judges strolled over to Howard and remarked: “Bob, that dog is nothing but a runner and will never amount to a damn. If you’re smart, you’ll get rid of him.”

This sterling bit of advice has plagued the judge ever since, and it’s doubtful that some dog men around the cornbelt circuit will ever forget it.

Two weeks after that trial, Buck won the open at Eagle, Wisconsin, displaying a breathtaking ability to handle and “take a line.” While he was still not sharp in marking, he was razor-keen in other departments. Howard says proudly: “I never claimed that Buck was the world’s greatest marker, but Lordy – the way that dog entered water, and the way he took a line!” The latter ability, by the way was one of Buck’s strongest. Another well-known trainer later remarked that if King Buck had “taken a line” to England, the Atlantic cable could have been laid along his course.

Two weeks after the Eagle trial, Buck won two second places and completed his field trial championship. People began to watch for him at trials and judges would hail Howard and ask after his “wonder dog.”

One of the men watching King Buck’s rise was John Olin of Alton, Illinois – founder of the Nilo Farms and Nilo Kennels. Olin was on the lookout for retrievers to stock his new kennel, and although he had never seen Buck in action he was impressed with the young dog’s record.

Grundwald had already refused several offers for King Buck, including one bid of $5,000. But when Olin topped that price with a satisfactory offer, Grunwald accepted.

In June, 1951, two months after Buck’s third birthday, he was delivered to Nilo manager T. W. “Cotton” Pershall at Winona, Minnesota. Although Howard had continued to run King Buck for about two weeks after the transaction, it was really Olin’s dog that won the field championship at Winona the day that Cotton Pershall led Buck away.

Pershall had frank misgivings about King Buck. The dog had sprung from good stock, but no other pup in the litter had shown any particular promise. Buck had been sold as a puppy for only $50, and the near-fatal bout of distemper could have left his health permanently scarred. So although Buck’s record was admittedly impressive, Cotton had reason to doubt that he was worth the price. But Olin was adamant, and had bought King Buck in spite of Cotton’s misgivings.

Waiting at Nilo were two other dogs; Hot Coffee of Random Lake and Freehaven Muscles. These Labradors had caught Pershall’s eye and the trainer was certain that Muscles’ steady, healthy background held greater promise that Buck’s. There was a tacit understanding around Nilo that Freehaven Muscles was Cotton’s choice, and that King Buck was “J. M.’s dog.” Both men were right. Freehaven Muscles was a fine retriever – the sort that perpetuates fine bloodlines. But King Buck – the mid-sized Labrador of the fifty-dollar puppy price – was the sort that makes history.

Pershall is a champion-maker. By 1951 he had already trained retrievers that had taken five national titles, great dogs that included Shed of Arden, Bracken’s Sweep, and Marvadel Black Gum. He had also trained Tar of Arden, judged as the outstanding retriever of 1941. Under Cotton’s expert hand the maturing King Buck began to catch fire. Even the astrology was favorable, for Pershall and Buck were both born on April 3.

Pershall is a champion-maker. By 1951 he had already trained retrievers that had taken five national titles, great dogs that included Shed of Arden, Bracken’s Sweep, and Marvadel Black Gum. He had also trained Tar of Arden, judged as the outstanding retriever of 1941. Under Cotton’s expert hand the maturing King Buck began to catch fire. Even the astrology was favorable, for Pershall and Buck were both born on April 3.

In spring, 1951, King Buck won a first, two seconds and a third place. That fall he took another first, a third and a fourth, and completed ten of eleven series of the 1951 National Championship Stake – placing high among the nation’s top retrievers. He made a slow start in 1952 with a first and a third in the spring. In autumn he won a first, second and fourth. In November he again entered the world series of retrievers at Weldon Spring, Missouri.

That “National” ran three days in late November and King Buck had his work cut out for him: of the thirty-two dogs entered, only one was dropped in the first six series of the grueling contest. But, as always, Buck bore down when it counted.

“He seemed to have some power of knowing when the competition was really rough, and he always came through.” Cotton Pershall said later. “He wasn’t a big dog as Labs go, but he had great style. Always quiet and well-behaved, not excitable nor flashy. He just went steadily ahead with his job, series after series, whether on land or water.”

Buck put on a show at Weldon Spring. He obeyed superbly, responded sharply to commands, and made direct, perfect retrieves. Right down to the final test, when he completed the tenth series with a 225-yard water retrieve, he performed like a champion. He had never been sharper, and although it wasn’t a one-dog trial in any sense, there was never really any serious doubt of the outcome after the first few series. At the beginning of the trial King Buck had been just another dog in the pack. Three days later he was officially the finest field trial retriever in the nation.

Judges at that 1952 National were Thomas Wright Merritt of Chicago; J. Everett Lofland of Dover, Delaware; and Claude Bekins of Seattle. Merritt awarded Buck 97.9 points, Lofland credited him with a score of 98 and Bekins scored him at 99. Of a possible 300 points, King Buck had earned 294.9. The judges were vastly impressed with the new champion and vied with each other for superlatives. On his card Lofland jotted such praise as: “Much style and hustle, lots of guts, very sharp, perfect response. The winner without question.” Bekins simply noted: “In all my experience, King Buck gave the best performance throughout the trial that I have ever seen . . . “

At the end came an appropriate salute. A flock of Canada geese and several hundred mallards rose from one of the nearby refuge ponds and swung just out of gun range over the five hundred watchers in the gallery. That was all John Olin and King Buck needed; soon after the trophy was awarded, the man and his dog broke away from the well-wishers and headed for Arkansas. Olin wished to see if Buck could perform as well in flooded timber as before a field trial gallery, and it transpired that the dog could and did.

At the end came an appropriate salute. A flock of Canada geese and several hundred mallards rose from one of the nearby refuge ponds and swung just out of gun range over the five hundred watchers in the gallery. That was all John Olin and King Buck needed; soon after the trophy was awarded, the man and his dog broke away from the well-wishers and headed for Arkansas. Olin wished to see if Buck could perform as well in flooded timber as before a field trial gallery, and it transpired that the dog could and did.

When Olin and his dog arrived in Stuttgart – the “duck Hunting Capital of The World” – the National Duck Calling championship was just ending. Buck couldn’t have had a more enthusiastic welcome; when he was introduced as the new national champion he was given a booming ovation by hundreds of the nation’s finest waterfowlers.

John Olin walked into the lobby of the Riceland Hotel that evening with Buck at heel, wreathed in an aura of excitement and as fragrant as a hot mince pie. A friend later observed that “it was the tiredest dog I’d ever seen, and John was as relaxed as a man can be and still ambulate.”

Buck was the center of attention that night at a general rejoicing and was even offered some champagne in his silver trophy bowl. A champion athlete in training, he sensibly abstained. Olin poured out the champagne and filled the bowl with water, and after buck had quenched his thirst the bowl was refilled with champagne and passed among the guests as a communal toast to a great dog.

Buck was the center of attention that night at a general rejoicing and was even offered some champagne in his silver trophy bowl. A champion athlete in training, he sensibly abstained. Olin poured out the champagne and filled the bowl with water, and after buck had quenched his thirst the bowl was refilled with champagne and passed among the guests as a communal toast to a great dog.

One man refused the toast, saying; “I’ll not drink from that bowl after a dog has used it!!” At that time and place, the remark showed a signal lack of discretion. Under Olin’s withering glare, the guest was invited to leave the festivities and seek more antiseptic surroundings. For a moment there was even a distinct possibility that he might find such a germ-free climate in the local emergency ward.

Buck slept in John Olin’s hotel room that night – the first time that the dog had ever shared quarters with a human being.

The great Labrador was never much for show. Never during his lifetime did he posture, pose or give the slightest indication of public awareness. There wasn’t an ounce of ham in his makeup, and during his stay at the Riceland hotel he was thoroughly bored and made no pretense of his distaste for the limelight.

But the second day, when he was taken to flooded timber for his first adventure with wild ducks and wild duck-shooting, he came typically to life.

It was a field day, that shoot. The ducks were in, and they were working well. King buck was the only dog in the party, and he did all the retrieving for several gunners. He handled the wild mallards a s efficiently and cleanly as field trial birds, responding sharply to command and rejoicing in this work.

Years later, when an observer referred to some field trial retrievers as “hunting dogs,” Olin replied: “No, they aren’t really. They tend to be mechanical dogs, specializing in field trial work. That’s their job, not hunting.”

But of King Buck, Olin said: “He was one of the finest wild duck retrievers I have ever seen. In spite of his intense field trial training, he loved natural hunting. He used his head in the wild, just as in field trials. That first wild duck shoot was his day, every minute of it, and he made the most of it. He was beautiful to watch.”

But of King Buck, Olin said: “He was one of the finest wild duck retrievers I have ever seen. In spite of his intense field trial training, he loved natural hunting. He used his head in the wild, just as in field trials. That first wild duck shoot was his day, every minute of it, and he made the most of it. He was beautiful to watch.”

During the drive back to Stuttgart, as Buck lay on the front seat between Olin and guide Ronald Ahrens, the tired dog rested his head on his master’s leg – the first real sign of intimacy that he had ever awarded a man. It was that moment, after Buck’s first duck hunt, that sealed a bond between Olin and King Buck.

That night Buck didn’t sleep on the floor of Olin’s hotel room; he jumped up on the foot of his master’s bed and spent the night in style. And during the long years of field trial campaigns, whenever Buck and Olin were on the road together, it was always the same. Where the master slept, the dog slept.

Cotton Pershall arrived two days later to find King Buck sharing Olin’s bed, board and affection. Cotton had been unhappy about Buck’s Stuttgart trip in the first place, and when he saw the new champion being feted and petted, the professional trainer nearly went into orbit. That sort of thing simply isn’t done with a top field trial dog.

Cotton immediately checked Buck’s eyes, nose, paws and temperature, certain that sharing a warm hotel room – to say nothing of human affection – had been the ruination of the dog. But both John Olin and King Buck knew better. . .

Pershall continued to polish the champion that winter and spring, and although he was entered in no spring trials Buck swept the autumn campaigns with three first places. Then came his third National Championship Stake and the automatic defense of his new crown.

This contest was held at Easton, Maryland, in unseasonably warm weather and was a long, tough competition that went into overtime. For the first nine series of the 1953 National the defending champion made perfect scores but was pressed closely by a field that included such splendid dogs as Sprig of Swinomish, Marion’s Timothy, and Young Mint of Catawba. In the tenth series both Buck and Sprig needed special handling on a long marked triple, and the gap between their high scores and those of close competitors was narrowed. In the opinion of the judges, no dog finishing the tenth series had sufficient edge to be the winner. Two additional series were called.

This contest was held at Easton, Maryland, in unseasonably warm weather and was a long, tough competition that went into overtime. For the first nine series of the 1953 National the defending champion made perfect scores but was pressed closely by a field that included such splendid dogs as Sprig of Swinomish, Marion’s Timothy, and Young Mint of Catawba. In the tenth series both Buck and Sprig needed special handling on a long marked triple, and the gap between their high scores and those of close competitors was narrowed. In the opinion of the judges, no dog finishing the tenth series had sufficient edge to be the winner. Two additional series were called.

After “stubbing his toe” in the tenth series, Buck resumed his flawless performance and continued to blaze through the eleventh and twelfth series. Although two full extra series were mandatory, Buck’s competitors were actually eliminated in the eleventh – an exceptionally difficult three-bird land and water test. In the opinion of many, Buck performed perfectly in the test that eliminated his challengers.

One of the judges was Dr. George H. Gardner of Chicago, who commented in his field notes: “Class and style, beautiful line, excellent job!”

Another judge, Lewis E. Pierson, Jr. of Waterbury, Connecticut, wrote: “In eleven out of twelve series King Buck was faultless in every department on land and in the water - marking, bird sense, manners, steadiness, and control near at hand and far out. It was so apparent to all by the twelfth series that he was the clear and decisive winner that I am sure the official announcement came as an anticlimax.”

Buck was active in the national field trial campaigns for four years after that, still competing fiercely with younger dogs and established champions. As late as 1957, when he was nine years old, he not only qualified for the National Championship Stake but also completed eleven series out of twelve in the “National” and nearly won another title!

Buck was active in the national field trial campaigns for four years after that, still competing fiercely with younger dogs and established champions. As late as 1957, when he was nine years old, he not only qualified for the National Championship Stake but also completed eleven series out of twelve in the “National” and nearly won another title!

During his years at Nilo, King Buck finished 73 series of a possible 75 in seven consecutive runnings of the National Championship Stake. The only series that he failed to complete in those seven “Nationals” were the eleventh series in the 1951 contest and the twelfth series in 1957. No other retriever in history has successfully completed 63 consecutive series in the National Championship Stake.

He also completed ten series for handler John Olin in the 1957 American Amateur Retriever Trial, establishing a brilliant record of 83 completed series of a possible total of 85 series in national championship competition, including two successive national crowns!

There was one memorable fall day in 1955 when Buck retired three challenge trophies at once: the Guy S. Osborn Challenge Trophy, the Midwest Field Trial Club President’s Trophy, and the Glenairlie Challenge Trophy. The Osborn Trophy had remained unretired for eighteen years, the Midwest President’s Trophy for twenty years, and the Glenairlie Trophy for about eighteen years. To permanently claim any of these, an individual owner, kennel or dog was required to win the trophy three times. King Buck did just that, and took all three trophies out of circulation from the Midwest Field Trial Club!

But there was still one major honor in store for the famous old champion. In 1959 the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service paid tribute to retrievers and their role in waterfowl conservation by requiring that the design of the current Migratory Waterfowl Stamp be a retrieving dog at work. Maynard Reece, the famous Iowa artist whose work had already appeared on two “duck stamps,” came to Nilo and executed a watercolor study of King Buck. That was the winning entry; the 1959 duck stamp was a portrait of old Buck with a drake mallard in his mouth, set against a backdrop of windswept marsh grass and flaring ducks. It was the first time a dog had ever appeared on a United States stamp.

But there was still one major honor in store for the famous old champion. In 1959 the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service paid tribute to retrievers and their role in waterfowl conservation by requiring that the design of the current Migratory Waterfowl Stamp be a retrieving dog at work. Maynard Reece, the famous Iowa artist whose work had already appeared on two “duck stamps,” came to Nilo and executed a watercolor study of King Buck. That was the winning entry; the 1959 duck stamp was a portrait of old Buck with a drake mallard in his mouth, set against a backdrop of windswept marsh grass and flaring ducks. It was the first time a dog had ever appeared on a United States stamp.

Whitening about the muzzle, King Buck ruled Nilo Kennels for over a decade. In good weather he took the sun on the grassy lawn in front of the retriever quarters, or walked with slow dignity through the big exercise yard with the other dogs racing and tumbling about him. And even as his years bore him down, he remained chief champion of Nilo.

He died on March 28, 1962 – just one week before his fourteenth birthday – and was placed in a small crypt at the Kennels’ entrance, his statue above him. But that statue marks only the formal interment. A writer for the Portland Oregonian, Ben Hur Lampman, knew the place where dogs such as Buck are really buried:

. . . For if the dog be well remembered, if sometimes he leaps through your dreams actual as in life, eyes kindling, laughing, begging, it matters not where that dog sleeps. On a hill where the wind is unrebuked and the trees are roaring, or beside a stream he knew in puppyhood, or somewhere in the flatness of a pasture land where most exhilarating cattle graze. It is one to the dog, and all one to you, and nothing is gained and nothing lost – if memory lives. But there is one best place to bury a dog.

If you bury him in this spot, he will come to you when you call – come to you over the grim, dim frontiers of death, and down the well-remembered path and to your side again. And though you call a dozen living dogs to heel they shall not growl at him nor resent his coming, for he belongs there.

People may scoff at you, who see no lightest blade of grass bent by his footfall, who bear no whimper, people who may never really have had a dog. Smile at them, for you shall know something that is hidden from them.

The one best place to bury a good dog is in the heart of his master.

NILO FIELD TRIAL RECORD

OF

KING BUCK

|

SPRING, 1951: |

|

SPRING, 1955: |

|

|

Wisconsin Amateur Field Trial Club |

1st |

Midwest Field Trial Club (Open) |

2nd |

|

Northeastern Wisconsin Kennel Club |

2nd |

Wisconsin Amateur Field Trial Club (Open) |

1st |

|

Golden Retriever Club of America |

2nd |

|

|

|

American Amateur Retriever Club |

3rd |

FALL, 1955: |

|

|

|

|

Wisconsin Amateur Field Trial Club (Open) |

2nd |

|

FALL, 1951: |

|

Missouri Valley Hunt Club (Open) |

4th |

|

Wisconsin Amateur Field Trial Club |

3rd |

Northwest Iowa Dog Club (Open) |

2nd |

|

Missouri Valley Hunt Club |

4th |

Midwest Field Trial club (Open) |

1st |

|

Midwest Field Trial Club |

1st |

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club (Amateur) |

1st |

|

National Retriever Field Trial Club |

10 of 11 series |

National Retriever Field Trial Club 10 of 10 series |

10 or 10 series |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SPRING, 1952: |

|

SPRING, 1956: |

|

|

Northeastern Wisconsin Kennel Club |

1st |

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club (Open) |

1st |

|

Central Minnesota Retriever Club |

3rd |

Nebraska Dog & Hunt Club (Open) |

2nd |

|

|

|

Midwest Field Trial Club (Amateur) |

1st |

|

FALL, 1952: |

|

|

|

|

Manitowoc County Kennel Club |

1st |

FALL, 1956 |

|

|

Midwest Field Trial Club |

2nd |

Wolverine Retriever Club, Inc. (Open) |

1st |

|

Swamp Dog Club |

4th |

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club (Amateur) |

1st |

|

National Retriever Field Trial Club |

1st |

Midwest Field Trial Club (Open) |

3rd |

|

|

|

National Retriever Field Trial Club |

10 of 10 series |

|

FALL, 1953: |

|

|

|

|

Midwest Field Trial Club |

1st |

SPRING, 1957 |

|

|

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club |

1st |

Lone Star Retriever Club (Amateur) |

C.M. |

|

National Retriever Field Trial Club |

1st |

Port Arthur Retriever Club (Open) |

1st |

|

|

|

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club (Amateur) |

1st |

|

SPRING, 1954: |

|

Midwest Field Trial Club (Open) |

C.M. |

|

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club (Amateur) |

2nd |

Madison (Wisconsin) Retriever Club (Open) C.M. |

C.M. |

|

|

|

Golden Retriever Club of America (Open) |

1st |

|

FALL, 1954: |

|

|

|

|

Mississippi Valley Kennel Club (Open) |

3rd |

FALL, 1957 |

|

|

National Retriever Field Trial Club |

10 of 10 series |

Swamp dog retriever Trial (Open, Special) 3rd |

3rd |

|

|

|

National Retriever Field Trial Club |

11 of 12 series |

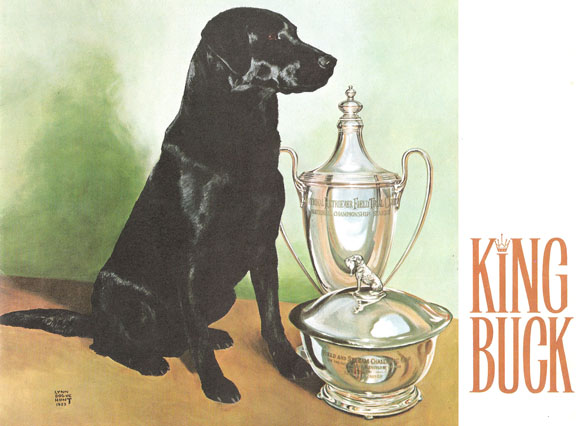

photo courtesy of Dr. Ed Kozicky

John Olin and King Buck at Nilo Farms