|

THE TOEPP GUNS OF ALL TIMES

a compilation of articles written by

Norman Wiltsey for Guns & Ammo (Oct., 1961)

Col. Charles Askins for American Rifleman (Feb., 1986)

From "Famous Guns From the Winchester Collection" (1958)

The Fabulous Toepperweins

by Dick Baldwin

AS LONG as there have been firearms, there have been exceptional marksmen to whom accurate shooting has become as instinctive as breathing. There were noted Indian fighters, scouts, buffalo hunters and gun fighters on both sides of the law who were almost unbelievably skillful. There were also sportsmen who gained uncanny finesse with their firearms and marksmen and trick shooters who made their livelihood giving awe-inspiring exhibitions.

At about the same time that a lithe. willowy wisp of a girl, Annie Oakley of Greenville, Ohio, came to the attention of circus and vaudeville marksman Frank Butler, who billed himself as the "World's Champion Rifle Shot," an Illinois sportsman, A. H. Bogardus established a record that neither Butler nor Miss Oakley, despite far more widespread publicity of their shooting prowess, ever matched. On the 4th of July in 1877, Bogardus, alternating with a pair of 12-gauge breech-loading shotguns, fired in rapid succession at 1000 212" diameter glass balls. He is reported to have missed only 27 of the 1000 shots, shattering one string of 303 of the glass spheres without a miss.

Twice more during the next year Bogardus turned his gun marksmanship on 1000 glass targets. In Cincinnati, in September. 1878, he scored 981 hits. Later that same year at Bradford, Pennsylvania, he blasted all but ten of the 1000. A year later Bogardus stretched his demonstration to 5000 glass balls, destroying all but 156.

During this same period, neither the "Great" Frank Butler, nor the widely publicized Buffalo Bill Cody, King of the Wild West touring shows, made any official challenge to top Bogardus' legitimate mark. Don't read into this comment any attempt to disparage Cody's widely lauded marksmanship. His record, even with his initial buffalo gun, a Springfield Model 1866 military rifle, was fantastic. In one eighteen-month period, Cody was credited with bringing in nearly 5000 buffalo to fulfill a meat contract he had made with the Kansas-Pacific Railroad. A fairly well authenticated report has it that with this same 1866 Springfield, Cody killed two horse thieves with a single shot. The slug fired from the rifle passed completely through one of the two thieves and downed the second.

Cody's favorite firearms, however, were Winchesters. Of the 1873 model, he was known to have owned at least a half dozen, a number of which are in private collections today. But once Cody left the frontier and his touring Wild West show had added to his fame, he was forced to resort to trick loads just as did others who gave fast action indoor shooting exhibitions before large audiences.

Reportedly Cody's 44/40 Winchester center fire cartridges were specially made and contained 20 grains (only a half load) of black powder and one-quarter of an ounce of chilled shot. Cody didn't have to resort to bird shot because he was a poor marksman but rather because firing solid bullets with a full powder charge in locations like Madison Square Garden would endanger audiences. Also making a sieve of roofs wouldn't for long meet with the approval of any building's owners.

Whether due to personal concern as to whether he could hold his own in an official match or more probably because he was canny enough to realize that already having an enviable reputation for marksmanship, he had far more to lose than gain by engaging in any competition. Cody is known only once to have shot a challenge match.

In that fiasco reportedly he and his opponent interspersed each gun shot with two fingers at a nearby bar so that Cody's defeat was not a true indication of his skill nor that of his opponent, but rather proof that his challenger was a better drinking man.

Despite her unquestioned ability as a marksman, few official Annie Oakley records were posted. Only twice did she officially put her highly publicized shooting skill on a block.

In 1883. a Dr. A. H. Ruth stole the nation's marksmanship limelight when he shot at 1000 hand-thrown glass balls and broke 984 of these with a .22 repeating rifle. Annie Oakley's press agent, sensing the publicity value of having her shoot for a record, persuaded her publicly to attempt to break Dr. Ruth's mark. In 1884, firing a .22 rifle under the same conditions, Annie nearly accomplished her goal. She smashed 943 of the 1000 glass balls. The 57 misses and failure by 31 shots to match Dr. Ruth didn't tarnish the sheen of her reputation -- after all shooting was still considered to be a man's sport.

That same year Miss Oakley also unsuccessfully tried to duplicate Bogardus' feat. Rotating between three 16-gauge shotguns, "Little Miss Sure Shot" fired at 5000 glass balls, missing 228, scoring 62 fewer hits than Bogardus had five years before but again she gained added luster by skilled press agentry.

The shooting of glass balls, of course, should not be confused with modern trap-shooting. Skeet target traps are adjusted to skim a clay pigeon at the height of 15 to 20 feet for a distance of 45 to 50 feet with the trap changing angle of throwing direction with each shot. The clay disk shooter does not know which way the target will soar. The old glass ball traps catapulted the target to a height of about 35 feet for a distance of about 35 feet from the trap. Hand thrown targets simulated this same procedure. The direction of target movement was much the same for each shot. So even when shooting at 5000 of these objects, the marksman knew almost exactly where his next target would be. Any of these shooting records placed greater emphasis on endurance and consistency rather than incorporating the added feature of quick directional reaction required for trapshooting. However, the sheer physical wear of these old-time shooting marathons was fantastic.

In 1885 a colorful dentist by the name of Dr. W. F. Carver gave up tooth extracting and gold bridgework in favor of the greater lure of silver to be gained from his uncanny marksmanship with a rifle. Doc Carver came pretty close to making good his claim of being the world's greatest rifle shot. In fact in the late nineteenth century the ex-forceps fumbler was for a time the undisputed ruler of the sharp-shooters' domain.

At a demonstration in a local armory at New Haven, Conn., Carver plinked away steadily with a .22 rifle for ten or eleven hours a day. At the end of six days he had shattered 55,151 glass balls with 60,016 shots. The next year at Minneapolis he tried again to smash his announced goal of 60,000 targets. This time the bicuspid mechanic racked up a total of 59,340 hits.

This looked like a record that would stand for all time but in 1889, a Captain Bartlett dethroned the dentist. Bartlett's performance was staged under even slightly more difficult conditions than Carver's dramatic display of marksmanship. In six days and six nights, Bartlett destroyed 59,720 composition balls, 2¼ inches in diameter, one-quarter inch less in size than the glass balls fired at by Carver.

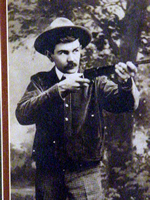

In 1869 at Boerne, Texas, Ad Toepperwein was born to the trigger, so to speak, for his father was a gunsmith, specializing in custom-built rifles for buffalo hunters.

The Chinese have a saying that "even the cobblestones in the street hate a ten-year-old boy." However, it wouldn't have been healthy for anyone to hate Ad Toepperwein at the age of ten (when his father died) for young Topperwein was already the equal of most men in handling firearms of all sorts. When Ad was six, his father made him a cross bow. At eight Ad already was out shooting most adult veterans with a big 14-gauge muzzle-loading shotgun. Shortly before his death, the senior Topperwein had given young Ad a Flobert .22 caliber single shot rifle and the youngster spent every spare moment plinking at targets until firing his .22 became as instinctive as eating or walking. It was that year that Ad, who had been impressed by publicity stories about the great Doc Carver, saw Buffalo Bill's top marksmen in action at a touring Wild West show.

Ad was given to bragging a bit after watching his idol that he would someday break the Doc's record. Later when Captain Bartlett became the king of the tossed targets, Ad boasted that someday he would beat the Captain's mark, too. Ad was given to bragging a bit after watching his idol that he would someday break the Doc's record. Later when Captain Bartlett became the king of the tossed targets, Ad boasted that someday he would beat the Captain's mark, too.

The world's marksmanship record was a long cry, however, from Ad's job in a San Antonio crockery shop. There he doubtless could have gotten a lot of target practice if the proprietor had been willing, but dusting instead of smashing crockery was a pretty dull job for a young boy with a gun and Ad finally quit. He didn't seem to progress much farther toward his quest of a world's marksmanship record when he landed a job as a newspaper cartoonist with the San Antonio Daily Express. The new job, however, did give him funds for practice ammunition and though he didn't realize it at the time, his talent for drawing was later to be transferred from pen to the sight end of his rifle and gain him an international audience for his cartooning artistry.

Shortly before he was twenty Ad was booked as local talent into a San Antonio theater. The theater's manager George Walker was so impressed by Ad's marksmanship that he paid Ad's expenses to New York, hoping to place Ad on the vaudeville circuit.

New York City, and vaudeville everywhere for that matter, had nearly as many trick and fancy shooters as it did banjo players. The jaundiced-eyed vaudeville bookers who refused to follow a banjo act with a banjo act, were unimpressed by the Texas triggerman who was just another would-be Keith's circuit target trouper to them and no more unique than a trained seal. New York City, and vaudeville everywhere for that matter, had nearly as many trick and fancy shooters as it did banjo players. The jaundiced-eyed vaudeville bookers who refused to follow a banjo act with a banjo act, were unimpressed by the Texas triggerman who was just another would-be Keith's circuit target trouper to them and no more unique than a trained seal.

Topperwein and his potential manager, Walker, gambled their last few dollars and persuaded a booking agent for the B. F. Keith vaudeville circuit to accompany them at their expense to Coney Island. Up and down the shooting gallery lanes at Coney, Topperwein proceeded to blow dime after dime's worth of ammunition blasting every clay pipe, duck, glass ball in each of the galleries in succession. Within fifteen minutes his amazing marksmanship had gathered a traffic-jamming throng as the Pied Piper of Triggerdom proceeded to temporarily bankrupt each shooting pitch in turn.

Finally the word spread throughout the whole arcade area and the galleries still to be tested by Topps closed their doors. The Keith's agent agreed that Topp's skill was a bit more unique than ball balancing on a seal's nose and that Ad's trigger finger held more audience lure than a banjo pick. Topperwein's professional career was under way. Finally the word spread throughout the whole arcade area and the galleries still to be tested by Topps closed their doors. The Keith's agent agreed that Topp's skill was a bit more unique than ball balancing on a seal's nose and that Ad's trigger finger held more audience lure than a banjo pick. Topperwein's professional career was under way.

For the next two years Topps filled in at minstrel shows and did his stint of on-stage marksmanship along with trained dog acts and jugglers until the greater freedom of shooting expression was offered to him as a star with the Orrin Brothers Circus. For the next eight years, he was featured under the canvas in nearly every state in the country as well as in Mexico. Twice south of the border Topps extended his magical touch on the trigger to "miracles."

On one occasion a local Mexican police official asked Topps to shoot at some silver coins for souvenirs. The chief tossed three silver pesos into the air in rapid succession. Ad scored three hits before the coins reached the ground, winging the bent currency out of the local bull ring. Unknown to Ad at the time, a poverty-stricken peon had been praying for help. As she sat just outside the adobe walls of the local amphitheater, gazing heavenward and unclasped her weathered hands, a peso dropped into her outstretched palm. Another coin jingled to the pavement at her feet. Her prayers had been answered by the miracle performer Topperwein.

During another barnstorming stint on the bull ring circuit, Ad broke one of his cardinal safety rules. This was the only time during his entire shooting career that Ad fired at a distant target without checking first to be sure no one was in the vicinity of his firing. The circus troupe, en route between performances, was passing an apparently abandoned mission a hundred yards distant on a hillside. One of the members of Ad's party challenged him to hit a bell partially obscured in the mission tower. Ad compensated for what he considered would be the trajectory of his .22 short for the distance. He fired and missed. Instinctively he corrected for his second shot and the bell pealed. Ad followed up with four more shots and the bell chimed rhythmically. Unknown to Ad the clapper of the bell had long been missing. The tiny church's parishioners were too poor to replace it and had long before become resigned to their muted church tower. Word of the miracle of the ringing of the clapper less bell spread rapidly. Within days a tremendous revival of interest occurred in the local church. Pilgrimages were formed and the long impoverished mission gained needed financial help. During another barnstorming stint on the bull ring circuit, Ad broke one of his cardinal safety rules. This was the only time during his entire shooting career that Ad fired at a distant target without checking first to be sure no one was in the vicinity of his firing. The circus troupe, en route between performances, was passing an apparently abandoned mission a hundred yards distant on a hillside. One of the members of Ad's party challenged him to hit a bell partially obscured in the mission tower. Ad compensated for what he considered would be the trajectory of his .22 short for the distance. He fired and missed. Instinctively he corrected for his second shot and the bell pealed. Ad followed up with four more shots and the bell chimed rhythmically. Unknown to Ad the clapper of the bell had long been missing. The tiny church's parishioners were too poor to replace it and had long before become resigned to their muted church tower. Word of the miracle of the ringing of the clapper less bell spread rapidly. Within days a tremendous revival of interest occurred in the local church. Pilgrimages were formed and the long impoverished mission gained needed financial help.

Despite his success in both vaudeville and circus, Ad's ambition to gain the world's marksmanship title had not been fulfilled. His interest had even waned somewhat as his performances became monotonously mechanical. Then in 1901 he was offered and accepted a contract with the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. He gave up his free-lance demonstrations to become a contract exhibition shooter. At 91, the venerable champion looked back over the long trail with fond nostalgia. "I'd do it all over again if I had the chance - but this time around I would stress even more the importance - the vital importance - of every American boy owning a rifle and knowing how to handle it. Working with Winchester as exhibition marksman brought me all I ever wanted; a wonderful wife, the world's rifle shooting championship, travel, good friends and a good living."

The dearest wish of Ad Toepperwein's heart was "That every American citizen in good standing shall, in accordance with Article Two of our Bill of Rights, be allowed to keep and bear arms, and that this Constitutional right shall not be infringed! No dictator will ever meddle with a whole nation of marksmen."

"For proof, look at Switzerland. Every man in Switzerland over sixteen is a trained soldier, with his rifle and marching gear ready at a moment's notice. Even madman Hitler wanted no part of the sharpshooting Swiss! America could be another Switzerland, if only our lawmakers had the brains and vision to take action. The nation's future existence may depend on it." "For proof, look at Switzerland. Every man in Switzerland over sixteen is a trained soldier, with his rifle and marching gear ready at a moment's notice. Even madman Hitler wanted no part of the sharpshooting Swiss! America could be another Switzerland, if only our lawmakers had the brains and vision to take action. The nation's future existence may depend on it."

For nearly a year Ad did more than a creditable job demonstrating his employer's wares, but during a visit to the New Haven plant in 1902, he met a vivacious 18-year-old redhead, Elizabeth Servaty, who was working as a .22 caliber cartridge assembler. Oddly enough Topps didn't meet his future wife at the Winchester plant but rather at the pump in the New Haven Common. A few weeks later they married and Ad suddenly had a new incentive to strive for even greater skill with firearms.

Elizabeth had never fired a gun before her marriage but enthusiastically joined Ad in his exhibition tours and showed no inclination to remain just an admirer in the audience. Toepperwein described their relationship: "Well sir, to make a short story shorter, we hit it off right away and were married a few weeks later. It sure pleased me when she took an interest in my shooting - most women were scared of guns in those days, you know. I taught her to shoot and soon after we were married Elizabeth was part of my act on my tours, shooting one-inch pieces of chalk from between my fingers, shooting empty shells off my fingers, and other feats of skill. Later on, she won the title of world's champion woman marksman."

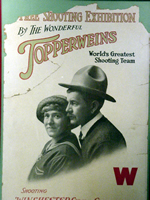

"Winchester signed her too and we became widely known as the world's greatest shooting team - The Famous Topperweins. Man, those were the days! Whole towns turned out to see us perform; schools were closed in order that the kids might come and witness the crack shooting exhibitions." "Winchester signed her too and we became widely known as the world's greatest shooting team - The Famous Topperweins. Man, those were the days! Whole towns turned out to see us perform; schools were closed in order that the kids might come and witness the crack shooting exhibitions."

From a Winchester brochure of the period:

"Seeing the Topperwein shooting exhibition is like going to a circus - a rapid succession of thrills and exciting feats, each more unbelievable than the one before, presented to you by this marvelous pair of shooters with rifle, pistol and shotgun ...These gun wizards put on a program full of variety from the opening gun until the last shot is fired. They shoot at all kinds of objects from every imaginable position - with rifle, pistol and shotgun.

"Clay pigeons - wooden blocks - composition balls - metal discs - marbles, etc; even apples, oranges, real hen eggs - all are shattered with different types of guns. Sometimes two- three -four-and even five targets are in the air at the same time, only to be broken before they fall back to mother earth." "Clay pigeons - wooden blocks - composition balls - metal discs - marbles, etc; even apples, oranges, real hen eggs - all are shattered with different types of guns. Sometimes two- three -four-and even five targets are in the air at the same time, only to be broken before they fall back to mother earth."

It has always been a debatable question as to which of the Topperweins is the better shot, Mr. or Mrs. While both do the most remarkable shooting stunts, each has a few tough ones which the other hesitates to try, so it is up to you to come and see for yourself. All America came to see for itself - and the friendly family argument was still unresolved at Mrs. Elizabeth (Plinky) Topperwein's death in 1945. When the question was posed to Ad, he responded: "Well," he grinned, "like the booklet says, I was best at some feats and she was best at others. Reckon it was a toss-up between us." Topperweins is the better shot, Mr. or Mrs. While both do the most remarkable shooting stunts, each has a few tough ones which the other hesitates to try, so it is up to you to come and see for yourself. All America came to see for itself - and the friendly family argument was still unresolved at Mrs. Elizabeth (Plinky) Topperwein's death in 1945. When the question was posed to Ad, he responded: "Well," he grinned, "like the booklet says, I was best at some feats and she was best at others. Reckon it was a toss-up between us."

"I'll tell you this: She could shoot smoke-rings around Annie Oakley or any other woman marksman who ever lived! Let me give you just a few of her records: Her best pistol score: one hundred consecutive shots fired into a five-inch diameter spot at 25 yards. Best rifle score on flying targets was 1460 straight hits on 21/2-inch wooden blocks thrown into the air 25 feet from her firing position. At Plinky's first attempt at trap shooting at the old DuPont Gun Club in St. Loums, she scored 86 of 100. She was the first woman ever to score a perfect 100 at clay pigeons. Later she scored 200 straight twelve times and "I'll tell you this: She could shoot smoke-rings around Annie Oakley or any other woman marksman who ever lived! Let me give you just a few of her records: Her best pistol score: one hundred consecutive shots fired into a five-inch diameter spot at 25 yards. Best rifle score on flying targets was 1460 straight hits on 21/2-inch wooden blocks thrown into the air 25 feet from her firing position. At Plinky's first attempt at trap shooting at the old DuPont Gun Club in St. Loums, she scored 86 of 100. She was the first woman ever to score a perfect 100 at clay pigeons. Later she scored 200 straight twelve times and  later rung up 367 consecutive hits. "A hole-in-one in golf is just about like hitting a hundred straight targets in shooting. My wife Plinky did this 193 times in competition." later rung up 367 consecutive hits. "A hole-in-one in golf is just about like hitting a hundred straight targets in shooting. My wife Plinky did this 193 times in competition."

Until her death in 1945, Plinky continued to be tops in women's shooting, with either a shotgun, rifle or pistol. With a .38 Colt at 25 yards, she once turned in a score of 497 out of a possible 500, closely approximating military timed fire. With one string of 50 shots at a far higher rate than timed fire, she scored 492. For more about Plinky Toepperwein, see:

http://www.traphof.org/inductees/topperwein.htm

and: http://www.traphof.org/roadtoyesterday/november2000.htm

One of Ad's first large assignments for Winchester was at the World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904. There he established his first official record by smashing 3507 21/4 inch diameter aerial composition targets without a miss. He began to think again of the Carver and Bartlett records longingly and of his youthful claims that someday he would top them. Without publicly admitting it, after his St. Louis record, Toepp began to train for a try at the Bartlett or Carver scores. In 1906 he shot at 20,000 2¼ inch wooden blocks during a period of three days' shooting and scored 19,990 hits. He was sure then that all he needed was the time and proper arrangements to make his official bid to better Carver's and Bartlett's records.

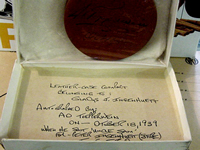

Finally in San Antonio, on December 13, 1907, at 9:00 o'clock in the morning, Toepps was ready to make good the boast he had made nearly fifteen years earlier. His preparations were painstaking. He had hired three young husky boys to toss his targets and 60,000 21/4 inch Texas white pine wooden blocks were stacked in a huge mound at the local fair grounds. A score keeper, judge and referee had been engaged to keep an official account of each shot.

Toepperwein on his eighty-eighth birthday in 1957 recounted the story of the official event.

"I will admit," he said, "that when I saw this big pile of blocks which had been delivered to the fair grounds, I had some misgivings. Would I be able to go through with it? And I did not sleep very well that night. Yet I was in perfect physical condition and perfect shooting form for I had been shooting daily for a number of years.

"Promptly at 9:00 o'clock on the 13th I fired my first shot. I continued to shoot until twelve o'clock noon when we stopped for an hour for lunch and a little rest for my target throwers. We resumed the shooting again at one o'clock sharp and continued shooting until five o'clock that afternoon. I followed this schedule and program accurately for the next ten days from December 13th to December 22nd, a total of 68½ hours. I did not shoot over seven hours a day on any day, with the exception of the last day, when I only shot for 5½ hours. I had shot up every cartridge I had and all that I could purchase in San Antonio.

"During these ten days' shooting, I shot a total of 72,500 targets. I missed four out of the first 50,000 and nine out of the total of 72,500."

Scores for Ad's ten days' shooting were as follows:

Date Targets shot at Number missed

Dec. 13th 7,500 0

Dec. 14th 7,000 1

Dec. 15th 7,500 0

Dec. 16th 7,000 2

Dec. 17th 8,000 0

Dec. 18th 7,000 1

Dec. 19th 7,000 0

Dec. 20th 7,000 4

Dec. 21st 8,000 0

Dec. 22nd 6,500 1

Total 72,500 9

"On the 20th," he continued, "I had my worst day when I missed four targets. The weather during the entire ten days was very bad, cloudy and chilly, with three days of almost continued drizzle rain, which did not help matters much. One of the boys offered me his raincoat, but I was afraid that it would hamper my shooting, so I took my medicine while the spectators stood about under umbrellas and nearby shelters.

"My equipment during the shoot consisted of three Model .03 Winchester 22 Automatic rifles and Winchester ammunition. These rifles held ten cartridges in the magazine. In order to save time in loading, we used loading tubes, which held ten cartridges, and all I had to do was to open the magazine and reload the rifle with ten cartridges. This operation only took up five or six seconds. I loaded the guns myself and changed guns every 500 shots, because in such rapid shooting, the barrels would be pretty hot. I had no trouble whatsoever with the guns operating. They worked beautifully throughout all the shoot without a single malfunction or hang-up. The breach mechanism was cleaned every night to remove powder residue: barrels were never touched.

"We had three men to pitch up targets, changing every 500 shots, in order to keep them from getting too tired and to make it easier for them to throw the targets with some regularity and speed. These targets were thrown into the air to a height of between thirty and thirty-five feet, twenty-five feet from where I was standing and as rapidly as possible. Although these young men had a pretty tiresome job, there was no complaint, and they cooperated with me in every way. They became so accurate in throwing that I was able to shoot at practically every target they threw. It was only in the very beginning that I refused a few of them because they were thrown very much out of line.

"As I ran way ahead of my supposed schedule for the first few days, we were running short of blocks toward the end, and the boys selected the blocks that were not mutilated too much for the rest of the score. Some of these blocks toward the end were rather small, but I was lucky, and I don't think I missed any on that account. The misses that I made were mostly because my arm was so tired, and the gun seemed so heavy that I just couldn't get it into place.

"I went through this shoot the first few days without much discomfort. Of course I was tired, but I expected that. However, it was a fact that all during the ten days I had very little sleep. These blocks were so impressed on my memory that nights were simply nightmares, and for some time afterwards I still dreamed about shooting blocks. From the fourth day until the end.

I was in constant physical misery. My arms and shoulders ached, the muscles of my neck pained me, and I felt like somebody had pounded me all over the body. To add to this, the fingers and the wrist of my right hand cramped and caused me a great deal of pain. This was caused mostly because I have a habit of gripping my gun very tightly with my right hand, and doing so continuously caused the muscles of my fingers and wrist to cramp. Finally one of the boys suggested some hot water. They made a fire and put on a pail of water, into which I put my hand frequently to relieve the pain. I was not the only one that was uncomfortable. My boys that threw the targets were also suffering from stiff necks and pains in the arms. However, they did not complain and were on the job every minute. It was necessary for me to have a rubdown with the hot bath every night and another one in the morning to get myself ready for what was before me the next day.

"On the eighth day I passed Bartlett's record and the crowd cheered wildly. Some of the spectators begged me to stop at this point, but I was determined to continue as long as I could hold and aim a rifle and had cartridges to shoot. Fact is, I was in pretty sorry shape. For the last two nights I had been so stiff and sore that Plinky (his wife) had to undress me. I couldn't lower my arms below the waist and my shoulders were swollen and tightened. When I flexed my arms, a sharp cramp knotted the biceps of my right arm. By this time I had quite a beard, but I couldn't handle a razor so got a barber to shave me."

"The ninth day was pretty much of a blur to me; still I continued to fire away at those infernal targets. Eight thousand of them on this next to last day and I didn't miss a one! But I knew when I got home that night that I couldn't go on much longer. Still I wouldn't quit. I could barely eat and I had lost so much weight that I looked worse than any scarecrow you ever saw! My eyes were bloodshot and no longer came to a clean, sharp focus on the sights. Nights were filled with one long nightmare of flying blocks and the monotonous drone of the referees, "Hit-Hit-Hit." I found I could get my arms up to shoulder height and then could not lower them; and once brought back to waist height, I had the utmost difficulty in lifting them once more."

"The tenth morning the boys had to help me to the firing line. The officials asked me if I was able to continue and I said "Sure!" Then the blocks started sailing up and I started shooting. I don't remember much of the morning but that huge pile of wooden targets kept growing little by little. A hot lunch revived me some and I went back at it again after a short rest. I fired my last cartridge late in the afternoon, hitting the  target dead center and splitting it wide open. The boys rushed up to grab me just as I started to black out a little and then I knew it was all over. I would have liked to have gone on a while longer to have rung up 75,000 targets, but I was very tired, the day was very dark, and anyhow I was out of ammunition. So I had to let well enough alone: 72,500 targets shot at; 72,491 hits; nine misses. target dead center and splitting it wide open. The boys rushed up to grab me just as I started to black out a little and then I knew it was all over. I would have liked to have gone on a while longer to have rung up 75,000 targets, but I was very tired, the day was very dark, and anyhow I was out of ammunition. So I had to let well enough alone: 72,500 targets shot at; 72,491 hits; nine misses.

"Although all this occurred practically fifty years ago, it is all still very fresh in my memory, and I think these were the most eventful days in my entire life. From the standpoint of the number of targets shot, the number of targets hit, time consumed and targets hit successively without a miss, this score still stands today as the world's greatest rifle shooting performance."

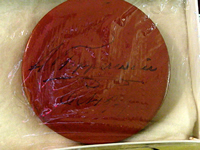

Drawing pictures with bullets was one of Ad's most popular stunts. While his art may not be as impressive as his 72,500 wooden block aerial target score that was 99.9875872% perfect, the keen-eyed Texan's bullet drawings of Uncle Sam, Sioux Indians in full war dress, Popeye, Jiggs, cowboys and ducks with 300 rapidly fired shots are prized possessions of gun clubs throughout the country. This remarkable gunsman made famous the Indian-head bullet drawing. With approximately 450 exceedingly well placed shots, the whole of them delivered in the space of a dozen minutes, he drew the perfect likeness of an Indian chieftain in full war bonnet regalia. In his heyday, Topperwein Drawing pictures with bullets was one of Ad's most popular stunts. While his art may not be as impressive as his 72,500 wooden block aerial target score that was 99.9875872% perfect, the keen-eyed Texan's bullet drawings of Uncle Sam, Sioux Indians in full war dress, Popeye, Jiggs, cowboys and ducks with 300 rapidly fired shots are prized possessions of gun clubs throughout the country. This remarkable gunsman made famous the Indian-head bullet drawing. With approximately 450 exceedingly well placed shots, the whole of them delivered in the space of a dozen minutes, he drew the perfect likeness of an Indian chieftain in full war bonnet regalia. In his heyday, Topperwein had many contemporaries, some of whom tried to emulate his Indian, but their efforts were crude indeed compared to his bullet work. Our Texan had been a cartoonist for a San Antonio newspaper before he took up his guns in the Winchester cause. This artistic background stood him in good stead when bullets replaced his pens and brushes. had many contemporaries, some of whom tried to emulate his Indian, but their efforts were crude indeed compared to his bullet work. Our Texan had been a cartoonist for a San Antonio newspaper before he took up his guns in the Winchester cause. This artistic background stood him in good stead when bullets replaced his pens and brushes.

His shooting was by no means confined to drawing bullet pictures. He would toss a .32-20 cartridge in the air and shoot the bullet out of the case. He would turn the Model '03 Winchester .22 automatic on its side, pull the trigger, and as the tiny empty was ejected, flip the rifle to his shoulder and hit it. He tossed washers in the air and shot through the hole in the middle. When the crowd cried that it was a fake, he would reach in the box and bring out a handful of washers with the holes covered with paper. The resulting display, the bullet neatly puncturing the paper, convinced the most doubting.

He stacked five clay pigeons on the stock of the Model 12 Scatter gun, heaved them a dozen feet into the air, then shuffling the slide like a demon, would break all five before any touched the ground.

He would ask the biggest man in the crowd to come forward and throw an egg for him. The egg would go so high some of the audience would lose sight of it. But not Topperwein. At the very top of its ascent the eagle-eyed exhibitionist would burst it with nothing more lethal than a dinky ½ ounce load of No. 9 shot from the pipsqueak .410 shotgun. He threw two clay targets, ran twenty feet, turned a somersault, snatched up his trusty shotgun and powdered both of 'em before either could hit the ground. Topperwein is more than six feet tall and was as agile as a circus acrobat.

His act also included the pistol and some of his best stunts were done with the belt gun. He would lay one six shooter over his shoulder pointed backward. A second would be aimed forward. The front-looking gun he aimed with his left eye, the backward pointing weapon was aimed with a mirror and the right eye. Try it sometime. When the two guns spoke, they always went right together and both targets were neatly transfixed.

He had a variation to this trick which was just about as impressive. He stood directly between two tin cans, each tin about 20 feet distant. He would take his two six shooters, fire at both cans at the identical moment and puncture both. This stunt involved aiming carefully at the right-hand can, and once this aim was good the hand, the arm and the gun had to remain absolutely fixed while he turned his head, aimed with the left gun and once this aim was okay, then to pull both triggers, neither weapon in the interim having swung wide of the marks.

Many of these phenomenal feats of Ad Toepperwein and his wife Plinky are available on VHS or DVD in the 1941 color video entitled: "The Topps for 40 Years--Ad and Plinky" from www.showmanshooter.com

One time Toepperwein was in Bisbee, Arizona, a miner's town and a tough spot some fifty years ago. He was doing his stuff before a crowd of miners and, like every gathering, he had a few hecklers. One of these kibitzers was especially obnoxious. He questioned the validity of most of the shots which Toepperwein made. Finally a big bumble bee came belching out of a hole at the shooter's feet.

"If you're so damn good, let's see you hit that bee," the miner bellowed.

Without so much as a second's delay, our Texan swung the little .22 auto-loader from the Indian head which he was fashioning and fired. The bullet did not hit the bee but neatly clipped off a wing. The insect tumbled to the ground. Without so much as a glance our shooter swung back to his bullet drawing, the rhythm of his firing scarcely upset. The crowd fairly howled. The heckler slunk off to the jeers of his fellows.

If any one man proved the efficiency of the repeating cartridge firearm, it was Ad Toepperwein who for 68½ hours averaged more than a thousand shots an hour. In 1959, Tom Frye, a Remington gun salesman,` girded up his loins, loaded up his Nylon 66 autos and shooting for 14 straight days succeeded in banging away at 100,010 wooden blocks. He hit all but six. The blocks were the same dimensions as the Toepperwein's targets but the shooting distance appears not to have been the regulation thirty feet. Photos of the Frye performance, which is most exemplary and in its way most surely constitutes a record, shows the blocks were thrown from alongside the shooter's shoulder. Toepperwein, it will be remembered, stationed his thrower some thirty feet directly to his front and had the targets heaved thirty feet into the air.

On January 5, 1960, Ad Toepperwein wrote the following letter of explanation about the Frye performance:

"It has been announced by the Remington Company that one of their shooting representatives recently shot 100,000 wooden blocks thrown into the air, missing but six. Most wonderful shooting, I would say, and I don't believe he could have hit more if he had set them on a fence post. All shooting with a rifle, pistol or shotgun is judged by distance. This is especially true when shooting a moving object. A score with a shotgun shot at 16 yards does not compare with one shot at twenty. And a score shot with a rifle at 50 yards does not equal one shot at a hundred. I have seen a great many pistol scores at pistol tournaments which produced perfect scores at 25 yards. At the same time I have never seen a perfect score made at fifty. In shooting my block record, which was shot over fifty years ago, I did everything to make it official. It was announced beforehand in all of the newspapers and was witnessed by the public. I had a referee and judge who checked every shot and a separate scorekeeper. The assistant who tossed up the blocks for me stood between 25 and 30 feet in front of me, measured, and tossed the blocks approximately 30 feet straight up in the air. Colonel Charley Askins, noted gun editor who lives in San Antonio, a few days ago received some photographs sent out by Remington. He came to see me the other day just before he set out for his African hunt and told me the pictures he has showed the assistants standing beside the shooter and the blocks were tossed in that manner close to the muzzle of the rifle ?- all of which makes this an entirely different story. This shooter, if he really shot 100,000 targets as he claimed he did, established more of an endurance test than accuracy. I am giving you this information so you may not form a concrete opinion of this man's wonderful performance. Keep your powder dry. Sincerely yours, Top "

Toepperwein followed the rules established by a group of sportswriters of the time. In Toepperwein's words: "A group of sportswriters, who, tired and disgusted with the conflicting claims of all the self-styled champions, suggested that all the prominent aerial target shooters of the times get together like sportsmen and gentlemen and draft a set of standard rules. Well, the `sportsmen and gentlemen' did considerable wrangling over conditions, but they did come up with a set of rules that satisfied everybody - more or less."

The original paper read as follows:

1. The shooter could use any kind of rifle shooting a solid ball.

2. The target was to be a standard glass or composition ball (Both were used as shotgun targets at that time).

3. The assistants tossing the targets were to stand between 25 and 30 feet in front of the shooter.

4. The targets were to be thrown into the air at a height of 25 to 30 feet.

5 There must be officials present at all matches; a judge, a referee, and a scorer to make each match one of record.

Toepperwein continued: "Carver, Bartlett, Dr. Ruth and Annie Oakley set their records by these rules. Ruth set the first official world's record at aerial targets with a rifle in 1883, when he broke 984 of 1000 glass balls. Annie Oakley tried to break his mark in 1884, but missed by 41 shots of tying Ruth's record. Annie's score was 943 hits out of 1000 shots." For more about Annie Oakley, see:

http://www.traphof.org/inductees/oakley.htm

"Doc Carver told me about the rules right here in San Antonio in 1897," Ad continued. "Fact is, he wrote 'em down for me and advised me to follow them exactly if I wanted any marks I made recognized as official. He called them by a fancy name: The Carver-Bartlett Rules for Aerial Target Shooting with the Rifle. But then Doc was a fancy fellow. .. I used the rules all the time I was working my way up to be champion."

|

When champion of champions Ad Topperwein retired from active campaigning for Winchester in 1951, it did not mean that he had retired from shooting and teaching shooting to others.  Herb Herb  Parsons, known as the "Showman Shooter", replaced Toepperwein giving shooting exhibitions all over the United States. Herb had seen Ad shoot in the 1930's at a grocery wholesale house in Somerville, Tennessee, and decided he wanted to do the same. Herb was first hired on as a salesman for Winchester-Western and then began exhibition shooting full time after Ad Toepperwein retired. He and Toepperwein corresponded regularly and he practiced new shots with "the professor" when he came to San Antonio, Texas. Herb preceded Toepperwein in death when he died in 1959 of complications from surgery. A Parsons video (Showman Shooter) and full account of his shooting career is available from www.showmanshooter.com Parsons, known as the "Showman Shooter", replaced Toepperwein giving shooting exhibitions all over the United States. Herb had seen Ad shoot in the 1930's at a grocery wholesale house in Somerville, Tennessee, and decided he wanted to do the same. Herb was first hired on as a salesman for Winchester-Western and then began exhibition shooting full time after Ad Toepperwein retired. He and Toepperwein corresponded regularly and he practiced new shots with "the professor" when he came to San Antonio, Texas. Herb preceded Toepperwein in death when he died in 1959 of complications from surgery. A Parsons video (Showman Shooter) and full account of his shooting career is available from www.showmanshooter.com

At his retirement, Ad Toepperwein was still connected with the Winchester-Western Company in an honorary and advisory capacity. Although temporarily sidelined by bad eyesight, he was keeping in shape for eye surgery in the near future by walking three miles a day and coaching the younger generation in the correct use of firearms. At his shooting lodge at Leon Springs, Texas, twenty miles north of San Antonio, he held free weekend classes for youths, young business men, soldiers from nearby military bases, and anyone else who was sincerely interested in the great American sport of rifle and pistol shooting. The old master talked and the young men listened intently and then went out on the firing line and practice carefully and patiently what he had taught. Not a man or boy who attended these weekend sessions doubted for a moment that "Uncle" Ad would be right up there with them firing away and cracking those aerial targets as of yore, once the eye doctors removed those pesky cataracts from his eyes.

Adolph Toepperwein died in 1962 at the age of 93.

THE FABULOUS TOPPERWEINS

by

Dick Baldwin

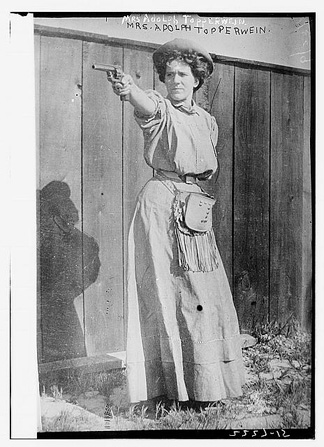

During the early years of the 20th century, a woman born in Germany was the best lady shooter in America. In the hay days of baseball's, "Ty Cobb" and horse racing's "Man O War", folks came to watch her shoot cigarettes from her husbands mouth with a handgun or perform other amazing acts of marksmanship. Back when men wore knickers with brightly colored stockings and it was illegal to shoot on Sundays, thousands came on Saturdays to see her perform.

Annie Oakley's shooting stories have been told countless times through books, movies and Broadway but this red headed woman was head and shoulders better. History will never forget Annie Oakley nor will they likely remember Elizabeth Servaty later known as Plinky Topperwein.

She was the first woman ever to be allowed to shoot in the Grand American,

the first woman to break 100 straight and the first lady to break 200.

Her story, marriage, and some 40 years of professional shooting for Winchester is as romantic and interesting as anything Hollywood has ever produced.

When he was 11 years old in 1880 Ad Topperwein of San Antonio Texas watched Doc Carver shoot aerial targets with a rifle. The six foot four inch Carver weighed some 200 pounds and long red hair fell in well combed ringlets over massive shoulders. Historians often referred to him as the most handsome man who ever held a gun. Carver initiated aerial targets using a rifle and at one time held most of the endurance and accuracy records for hand thrown rifle targets. After watching him perform, young Ad Topperwein knew what he wanted to do the rest of his life He wanted to do what Carver did.

By the time he was 16 he could duplicate everything Carver did. He had no coaching and learned by constant practicing even originating shots no one had done before. To supplement his income as a cartoonist for a local newspaper he began performing trick shooting exhibitions around San Antonio.

George Walker an opera house and vaudeville manager from San Antonio saw Ad Shoot and was impressed. During the days before motion pictures, vaudeville troupes kept America entertained. Trained dogs, leaping frogs, talking cats, and ventriloquists kept folks laughing. Walker convinced Topperwein that a shooting act would be very different and popular He went to New York every summer to book attractions for the coming season and in 1898 convinced Ad to go with him and he'd put him in the vaudeville business.

Gentleman, Jim Corbett, was the heavyweight boxing champion of the world and he was a friend of Walker's. The champion owned a resort on 42nd Street, and here, Adolph Topperwein was introduced to theatrical agents, sports writers and professional people. "The Texas Triggerman", as Walker called him, was the best shot the world has ever seen. His exaggeration of Ad's skill embarrassed the modest Texan.

A reporter from the New York World suggested they go to Coney Island where Mr. Topperwein could show what he could do with the rifle. During that time Coney Island had many shooting galleries. Targets consisted of small plaster birds, stars and pipes of clay. In the center was a three quarter inch bulls eye about 30 feet away with a sign that said, "you get a ten cent cigar every time you ring me." Topperwein picked up a Winchester Model 1890 . 22 caliber rifle and preceded to ring the bell consistently. The gallery operator began giving him cigars which were of no use to him as he didn't smoke so he gave them to the crowd and reporters who were watching his performance. By now, all the others had quit shooting, and were watching Ad break the clay pipes and plaster birds. The crowd whooped and hollered as Topperwein finished breaking the last object in the gallery. When it came time to settle up with the operator the poor fellow was so excited and confused he had forgotten to keep track of the number of shots. Mr. Walker gave him $5 and they went on to the next gallery with the crowd and reporters following. Here Ad did the same thing destroying everything in sight. But, this operator kept track of the shots and it cost Mr. Walker $8 and change.

The next morning in the New York World there was a four column story about "The boy from Texas who put shooting galleries out of business at Coney Island" It was all he needed to break into vaudeville and was hired by the Keith Circuit for $70 a week.

There were other shooting acts in vaudeville during those days but Topperwein's show was different and unique. One day when he was at a railroad station, he noticed the backs of the benches were perforated with holes forming the Texas Star and the name of the railroad. The holes suggested bullet holes to him. Having an artistic temperament, he began shooting five cornered stars, circles, triangles, and his initials with a .22 caliber rifle. He'd set up a piece of blank paper at about 25 feet and sitting on the ground sketch nearly any picture he wanted with bullet holes. One day he shot a picture of an Indian head and this is what separated him from other vaudeville shooting acts. No one could sketch an Indian with a lead pencil let alone shoot one with bullet holes.

He shot three times a day, six days a week. The audience loved those Indian heads. After two years, Orrin Brothers Circus of Mexico saw one of his acts and offered him one hundred pesos a week with expenses. They were referred to as "The Ringling Bros of Mexico", they were well financed and owned their own auditorium in Mexico City. He joined them in April of 1900 for a nine-month engagement.

When he returned to the United States on the last day of Dec, 1900 there was a letter waiting for him from the Winchester Repeating Arms Co. Several years before he had made the acquaintance of Jim Hildreth, Winchester's representative in the southern states. Hildreth knew what Topperwein could do with guns and the fact that he preferred Winchester firearms and ammunition. The letter said they would like to talk to him in New Haven, CT.

He arrived at the Winchester plant in January of 1901. He had never seen snow before and there was some three feet of it in New Haven. Very enthusiastically, he met with Mr. Bennett, the president, who offered him a job to take charge of their exhibit at the Pan American Exhibition in Buffalo, which started in April. It seems that John Cameron their representative at Buffalo would not be able to attend the exhibit all the time and when he wasn't there, Ad was in charge.

Topperwein was extremely disappointed. For sure, it was a foot in the door, but not what he expected. He wanted to shoot and there was to be no shooting at the exhibit. While in New Haven he was given a free run of the factory. He could go where he wanted, ask questions about the product and learn how to take guns apart and put them back together. Nights back in his hotel he studied the company catalog until he could recite what was on every page.

One day as he was going through the pistol loading room he stopped in front of a machine that loaded cartridges so quickly it fascinated him. He stood watching it for some time and didn't notice the operator.

When he did he looked right into a pair of laughing brown eyes. The young woman called him by name and he quickly withdrew. He went over to the foreman he knew pretty well and said he'd like to meet that girl But, it was against company rules to talk to operators. Ad insisted and the foreman led him back to the young woman. The foreman said, "Now don't talk to this girl - this is Mr. Topperwein, this is Miss Elizabeth Servaty, now come, let's go!" Ad didn't know it at the time but he had just met his future wife.

When finished at New Haven he went to the exhibition at Buffalo. Mr. Cameron would visit once a week to check up on things but the Winchester exhibit was Topperwein's responsibility. He remembered the day President William McKinley was assassinated and heard the shot that killed McKinley. Ad stayed in Buffalo for six months until the exhibition closed It was the only time in his life that he didn't shoot for six months. He said, "I didn't fire a shot. There was no shooting there, just an exhibition of guns. It was very hard on me, in fact it was awful."

While in Buffalo, he was in constant correspondence with Elizabeth. When he came back to New Haven he saw her again, met her people and went back home to Texas as an exhibition shooter for Winchester. The job he had always wanted. While in Buffalo, he was in constant correspondence with Elizabeth. When he came back to New Haven he saw her again, met her people and went back home to Texas as an exhibition shooter for Winchester. The job he had always wanted.

In January of 1903 he went back to New Haven and married Elizabeth on January eleventh. She had never been out of New Haven and things in San Antonio were strange and new to her.

His folks took a liking to his new wife and they lived with his mother and sister. Shortly after settling down Elizabeth expressed her interest in shooting. She didn't want to stay home while Ad was away giving shooting exhibitions. He started her with a little 22 and was amazed on how quickly she mastered things.

The most trouble he had was with the awkward way new shooters hold a gun. It took sometime to get the right poise and foot position but after she mastered it things commenced to go easy. He started her by letting her shoot a bullet hole into a blank piece of paper at about thirty feet. She would then shoot ten shots at this bullet hole to see how small a group she could make. All of this was offhand shooting. Her first groups were large but gradually they became smaller and smaller and soon all of them could be covered with a nickel. About a month after she began this kind of practice she started shooting chalk and crayons out of his hands and lips much to the horror of his mother and sister. It was a dangerous stunt but Ad knew she could hold that rifle steady as a rock.

After she accomplished her skill at stationary targets he started her on aerial shooting, beginning with large tin cans then smaller and smaller ones. The sound of the bullet hitting tin cans made what she described as "plinking". As the aerial practice continued, she began referring to it as Plinking. Ad picked up on this and started calling her "Plinky". The name became synonymous with her and for the remainder of her life she was known as Plinky Topperwein. Eventually the word was so commonly used in rifle shooting that it was listed in Webster's dictionary.

During the time Ad was on the road, sometimes for up to two months, Plinky would practice shooting everyday on a shooting range in their backyard. When he returned she would have many targets to show him and tales of success and failures.

She started her shotgun shooting with a little 20 gauge gun at St. Louis during the World's Fair. Alec Mermond was operating the DuPont Shooting Club and persuaded her to shoot a hundred targets with a gun that didn't fit her. She broke 83 of the first hundred she ever shot at.

When traveling in Texas Ad took her with him and paid her expenses. And, this kept the Topperwein family broke most of the time. She was not employed by Winchester and Ad often entered her in Trapshooting events as an amateur, shooting for targets only. This got expensive and for a while she stopped.

At the World's Fair in 1904 that she established her first world record for aerial targets by a woman. Using the new Winchester Model 03 .22 caliber auto loading rifle she broke 967 of 1,000 clay disks thrown into the air at 25 feet from where she stood. It took her one hour and thirty minutes to accomplish the feat. Ad paid for all her expenses during the six months they were at the World's Fair. They didn't want to be apart for so long a time and although they couldn't afford it he took her along.

As a result of her record shooting at St. Louis and other cities where she performed with Ad, Winchester made and arrangement with the Dead Shot Powder Company for Plinky to shoot their powder at the traps which made her a professional. This certainly helped financially and she now accompanied Ad on all his tours. As a result of her record shooting at St. Louis and other cities where she performed with Ad, Winchester made and arrangement with the Dead Shot Powder Company for Plinky to shoot their powder at the traps which made her a professional. This certainly helped financially and she now accompanied Ad on all his tours.

For 42 years they traveled the entire United States, Canada, and Mexico giving exhibitions of aerial rifle shooting and trapshooting. The arrangements with the Dead Shot Powder Co. were changed and she was made an employee of Winchester to shoot exhibitions with Ad.

She called him "Daddy" and he referred to her as "his current wife", but it was the only one he ever had. There might have been women who were better with a rifle than Plinky, or a pistol but there were none who could shoot a rifle, pistol, and shotgun better. She could handle all three like no other woman ever could.

When shooting buttons off his chest or cigarettes from his mouth with a handgun, she always kissed him first. Days when dangerous shots were to be performed and she didn't feel up to it she'd say, "Daddy, lets not do this act today." He never asked her why but for almost 50 years there was never an accident.

The first trophy Plinky ever won in open trapshooting competition was at Elliott's shooting park in Kansas City on Feb. 4, 1906. It was very cold and there was some six inches of snow on the ground but she broke 99x100 to beat the field and win the Ed O'Brien Trophy (Ed O'Brien was a Remington professional at the time). The next day's program called for a fifty bird live bird contest. The entry fee was high and the top pigeon shooters in the country were there. Plinky had never seen a live-bird shoot let alone shoot a live bird. Ad was reluctant putting up the rather large entry fee of $20 but Plinky wanted to shoot. Uncle Bob Elliott who owned the park told Ad he'd furnish the birds free if Plinky could shoot. So, that settled it. She killed the first seven pigeons before they got far in the air. The eighth was a snow white in-comer and it fell six feet from where she stood. The bird fluttered before it died and stained the snow red with blood. She walked off the line and all the coaxing in the world would not make her continue. Throughout the rest of her life, she never shot a live bird of any kind again.

At some gun clubs they attended Plinky would shoot 100 targets against four of the best shots the club had. Each man would shoot 25 targets and Plinky would shoot 100. She would shoot against one man at a time 25 targets each. The total of the four would be counted against her score of 100. She won nearly every match shot under these conditions. At one club, the four men were exceptionally good. The first broke 24, the next 25, the next 25, and the last 23 for a total of 96x100. Plinky broke 99 missing her 91st target.

Besides her shooting ability Plinky had other accomplishments. She was an excellent cook. When the Topperwein's were in hotels away from home and received a good meal she'd ask the waiter if she could talk to the cook and learn how to prepare that particular dish.

Plinky was also very clever working with a needle. It took her 10 years to finish a twelve-foot by six-foot table cloth of white Irish linen. On it, she embroidered the names of all towns in which they shot in the many years of touring the country. She carried it with here on the road and would work on it nights at hotels. Ad would sketch the name of the town in pencil and she would embroider around it.

Mrs. Topp, as she was referred to by many, also had an excellent singing voice but she did not play an instrument. Among her many trapshooter admirers was John Phillip Sousa, the famous band leader. While attending a trapshoot in Mississippi the crowds were large and the accommodations small. Private families took shooters into their homes for lodging This was a common practice in those days. The folks who took in the Topperwein's also had John Phillip Sousa as a guest. After a party someone suggested Sousa play a selection on the piano. He refused saying he didn't feel like it. When Plinky asked him to play he agreed but only if she would sing. They picked out one of Plinky's favorites. He played and she sang. When they got through he put both hands on her shoulders and said she could sing as well as she could shoot and anytime she got tired of shooting let him know and he'll put her on the road with his band.

T heir shooting days were fast and grueling. They performed each day and traveled by rail every night to the next city. This went on week after week with scarcely a day to rest. If it rained, they shot anyway In many western and southern towns they coming of the Topperwein's was proclaimed a holiday. Shops, stores, and schools were closed. Sometimes in a town of two or three thousand, as surrounding villages made it a holiday, would have an audience of three to four thousand. On southern church took advantage of their shooting by having an auction after the exhibition. heir shooting days were fast and grueling. They performed each day and traveled by rail every night to the next city. This went on week after week with scarcely a day to rest. If it rained, they shot anyway In many western and southern towns they coming of the Topperwein's was proclaimed a holiday. Shops, stores, and schools were closed. Sometimes in a town of two or three thousand, as surrounding villages made it a holiday, would have an audience of three to four thousand. On southern church took advantage of their shooting by having an auction after the exhibition.

Ladies of the church picked up all the targets they had shot at, tin cans, wooden blocks, bits of metal disk, cartridge casings, and shot shell hulls. The wooden blocks sometimes brought a quarter because they had a bullet hole in them, the shell that had been shot from Ad's fingers brought forty to fifty cents. Folds paid ten to fifteen cents for old tin cans shot full of holes. Ad's Indian head went off the auction block for $10.00 (two sold on E-Bay recently for $2,00.00). The church collected more money at the auction then the Sunday morning offering plate had received in over a month.

Plinky's trapshooting was practically all in competition. Both registered and unregistered targets were shot under all kinds of weather conditions. If she wasn't competing against local hotshots she was shooting against the best professionals in the country. Her favorite position in a squad was post #1. Shooting against the clock was popular in those days and records were kept on how long it took to break a certain number of targets. Big bets were made by the large audiences who always witnessed those events.

Shooting alone on June 1, 1906 at San Antonio she broke 485x500 16 yard targets in two hours and 25 minutes (about 25 targets every nine minutes). In 1908 she tried to beat the record of John W. Garrett of Colorado Springs who once broke 961 x 1000 in four hours and 35 minutes. Ad tried to talk her out of these endurance contests as they were extremely fatiguing. Shooting a 7 lb. Model 97 Winchester trap gun for over three straight hours was more than most men could handle. But, here German stubbornness prevailed and on Nov. 11, 1916 at Montgomery, Ala. She shot at 2,000 16 yard targets breaking 1, 952 in 5 hours and 20 minutes. Her average of 97.6 % established a new record. Actual shooting time was three hours fifteen minutes (25 targets shot at in less than 5 minutes) but time was lost unpacking targets and repairing the trap after only 300 birds. Her longest run was 280 straight. A large crowd was present and lots of money changed hands among the spectators. One unbelieving soul bet $100.00 that she would never shoot 2,000 shots and then to cover himself he bet another $100.00 that her score in the second 1,000 would be less than her first 1,000. He lost both bets as her score in the second 1,000 was two better than the first. At the time, this was the most number of trap targets shot at and broken by either man or woman in a single day. It might still be a woman's record. She used one Model 97 Winchester trap gun, which was cooled off after every 25 shots by dipping it in water. Plinky would never shoot with a coat no matter what the weather. Neither would she wear a glove. A blister formed on the palm of here left hand during the marathon shoot. After 1,000 shots, her entire palm was a solid blister and it broke open. The shooting stopped and a doctor bandaged the hand. After a half dozen shots she tore off the bandage because she said it worried here, the balance of here shooting was done with her hand raw and bleeding When she finished the doctor again treated her. It was three weeks before she could remove the bandage and begin shooting again.

When on tour through east Texas the Topperwein's stopped at a little town around noon time. It was a relatively small community but Winchester wanted them to put on an exhibition anyway. The town was crowded with people, horses, buggies and wagons as people from the surrounding countryside were attending a murder trial. While eating lunch at the only hotel the judge and prosecuting attorney were introduced to them. They inquired what time they were going to shoot. It seems the trial would not be over before the exhibition began. They were scheduled to leave on the 5 p.m. train to shoot at the next town the following day and it would be impossible to delay the exhibition until the trial was over.

The judge returned to the court house after lunch rapped on the bench with his gavel and told the crowd that due to matters of which he had just learned it will be necessary to adjourn until ten o'clock tomorrow.

Attorneys for the defense, the prosecutor, the jury, witnesses and spectators all moved to the shooting grounds where they enjoyed the exhibition.

They shot on a baseball diamond directly behind the town jail. While the Topperwein's were shooting the defendant in the murder case together with several other prisoners watched the show from the barred windows of their cells on the second floor. This could only happen in Texas! And, the result of the jury's verdict is unknown.

The Liggett Company once asked the Topperwein's to perform at a large druggists convention near Boston. Over two thousand Rexall druggists were present. Mr. Liggett was well acquainted with Winchester officials from the home office. He was also a personal friend of Calvin Coolidge who was the President of the United States at the time. So, he invited Calvin and Mrs. Coolidge to watch the show. Ad was told to hold up the exhibition until the Presidential yacht arrived which was to be announced by a cannon shot.

The weather looked bad. Heavy clouds and wind predicted a storm was soon to break. Ad and Plinky were anxious to start before the weather set in and had about given up that the presidential party would attend But, the President and Mrs. Coolidge did arrive and took from row seats.

The Topperwein's went through their regular shooting routines but every time they glanced over at the President he looked like a stone statue and quite bored. But, Mrs. Coolidge was over enthusiastic and applauded everything they did. It seemed that nothing they did could arouse old Calvin's interest. At one time, they thought he was asleep.

The show reached a point where Ad used the shotgun and eggs for targets. He would throw up 2, 3, 4, and then 5 breaking them all before they hit the ground. As a climax, he laid his gun on the ground, threw up an egg, ran fifty feet to the gun, picked it up and broke the egg before it hit the ground. Only then, did Calvin show any interest, he applauded.

After the exhibition, the Topperwein's were introduced to Mrs. Coolidge and the President. She was very pleased with the show saying it was the most wonderful thing she had ever seen. But, the President was less than enthused. After complimenting them on their shooting he told Ad it seemed to be a terrible waste of eggs!

In all the years of traveling the country doing just about the some type of shooting at many of the same places Annie Oakley and Plinky met but a single time. The Topperwein's were booked at a hotel resort in Portsmouth, New Hampshire called Wentworth-By-The Sea (it's still there but now a Marriott). Annie Oakley and her manager/husband Frank Butler had been there for sometime giving trapshooting instructions to ladies staying at the hotel. Their contract expires a week before Ad and Plinky were scheduled to perform but when they heard the Topperwein's were coming they stayed an extra week to watch them.

It was raining during the day of the exhibition but the grounds were filled to capacity. As was their usual routine. Plinky first shot 100 targets at the 16 yard line in a squad with the best local performers that could be found. She broke 96 which Ad considered excellent und the conditions. By the time the trick shooting started it was really pouring. Both Topperwein's were in top form that day and scarcely missed a shot. Annie and her husband watched the complete show. Right after the final shot Annie ran over to Plinky and said, Mrs. Topperwein, you're wet, your clothing is all soaked. I want you to come up to my room and I will fix you a cup of tea and I want to talk to you."

Ad's memoirs said Plinky was in Annie's room an hour or two. When she returned she told her husband that Annie told her she was the greatest shot she had ever seen and how she wished she was younger so the two could team up. Frank (Annie's husband) had told her about her shooting but she saw things today that she never imagined could be done. "I didn't think it possible for any woman to do shooting like you did!" And, Annie Oakley cried.

In all the years that followed Plinky and Annie corresponded through post cards and Christmas greetings but that was to be the only time they were ever together.

One of Ad's favorite Plinky stories happened in one of New Haven, CT's best hotels. They arrived late and had little choice of rooms. About two in the morning Plinky woke up screaming there was a rat in their bed. Ad tried to convince her she was dreaming but about ten minutes later he realized she was right. He jumped out of bed and turned on the light in time to see Mr. Rat scurry along the wall to an opening in the floor made for a gas pipe. When they demanded another room the night clerk informed them there were no rats in the hotel and there were no more rooms. The hotel was filled.

Plinky took out a .44 Smith and Wesson Russian revolver that they used in an act, turned on a light and waited for Mr. Rat to appear. The whole thing seemed kind of funny to Ad, but he wanted to show that smart aleck night clerk that his hotel indeed had rats. It wasn't long before Mr. Rat reappeared and Plinky shot him right in the middle. The .44 bullet splattered him all over the wall and in a small room the shot sounded like a cannon. Immediately, people were awakened and doors were slamming. The night clerk was at their room in a matter of minutes wanting to know what the shooting was about. Ad said they shot a rat. The clerk again said there were no rats in his hotel. Ad told the clerk to wait a minute, took a newspaper and wrapped up what was left of the rat, opened the door about six inches and said, " Now you take this downstairs, examine it and see what you think it is." And he slammed the door in his face. Plinky sat in a rocking chair the rest of the night holding that .44 Russian but no more rats appeared as Ad used some towels to plug up the hole

The morning after all this, a chambermaid told them there were vacant rooms on their floor. The clerk was just too lazy to move them. The next morning the hotel proprietor was behind the desk. He was red faced with anger over the previous nights shooting and threatened the Topperwein's with arrest. Ad told him to do what he had to do to them reminded him he was an employee of Winchester and the morning reporter for the local paper was a friend of his. Topperwein assured the proprietor that folks around New Haven would find a newspaper story about rats in his hotel quite amusing. There was an immediate change in attitude and a half hearted apology. He changed their room to a first floor suite and couldn't do enough for them during the rest of the time they stayed there.

During World War II Plinky and Ad performed exhibitions in front of hundreds of thousands of soldiers at basic training camps through out America. Ad was now in his seventies and Plinky eleven years his junior He could still stand on his head and break clay targets in the air or do three somersaults and hit hand thrown wooden blocks with a rifle. But, the strain of some 40 years of hectic travel caught up with Plinky. In early January, 1945, she suffered a heart attack and on the 20th day of the month, died.

A Western-Winchester employee newspaper from East Alton, Ill. Summed things up pretty well when it said in part:

The world's greatest woman shooter isn't with us anymore. She passed away quietly in San Antonio, her only regret that she would be parted temporarily from her beloved "Daddy".

Perhaps people may forget that Mrs. Topperwein once broke 367 clay targets in a row; that she broke 200 straight 14 ties and 100 straight on more than 200 occasions.

But, not a living soul who knew "Plinky" will ever forget her great warm heart, which she wore openly on her sleeve in adoration of her accomplished husband. And, nobody will forget her ready wit and her firm handclasp, and her cheerful voice, and the way her eyes crinkled in the ever recurring smile.

Ad took Plinky's untimely passing extremely hard. To make matters worse, he began to have trouble seeing well shortly after her death. Doctors predicted the glaucoma would eventually cause blindness. Years of shooting also affected his hearing but he continued to keep an upbeat attitude. Ad was active with the shooting fraternity for 17 years after Plinky's death. He taught shooting to youngsters even though he was virtually blind. Big time gun writers of his day often came to visit and he'd tell them about the old days on the road for Winchester. He walked three miles a day until he was 92 years old. The end finally came on March 4, 1962 and with it ended an era in America that most of us can only visualize.

Many of us missed out on lots of exciting things by, unfortunately, being born too late. Ad and Plinky are prime examples. Their likes will never be seen again.

===============================

by Dick Baldwin (1937 - 2006) Director, Trapshooting Hall of Fame

published in: 2006 TRAP & FIELD, Volume 183, Number 11 & 12.

The 2005 book, The Road to Yesterday, a compilation of Dick Baldwin's TRAP & FIELD columns plus new material, can be ordered on the web at: http://www.traphof.org/baldwin-book/sales.htm

|